The Bagpipe Society

Hale the Piper (cont...) and other Peak Pipers

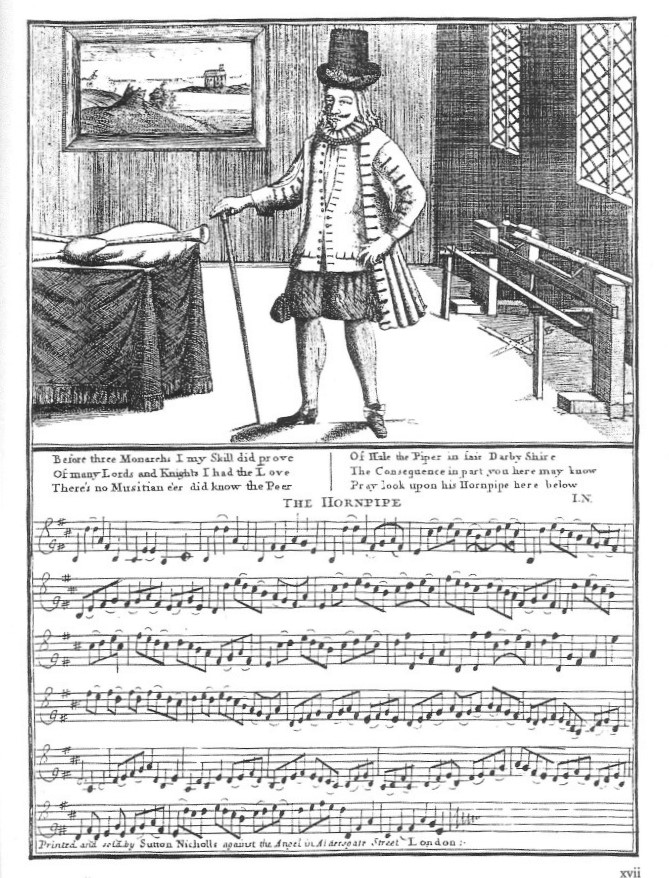

Long standing BagSoc members may remember that 7 years ago I wrote an article for Chanter about Eric’s and my discovery of the portrait of Hale the Piper. For those unfamiliar with either Hale or the story, I will give a little background information. The full article, if you’re interested, is available on the website here: http://bit.ly/Chanter111. Hale the Piper is well known amongst fans of early English bagpiping as well as lovers of 3/2 hornpipes. We know about Hale through two engravings, one depicting him dressed in his finery, standing next to his lathe and a keyed bagpipe. Below him is a verse stating that he was a skilled musician who had played in front of three monarchs. At the bottom page is a tune entitled “The Hornpipe”, which subsequently became known at The Derbyshire Hornpipe. There is also a later re-imagining of the engraving, which is basically similar but with small, distinct changes to the original.

Hale has always been something of an enigma – the eccentric clothing, the lathe and the bagpipe – together with a hornpipe which can’t be played on a standard set of bagpipes. So, a chance discovery of a portrait of a man wearing identical clothing to that in the engraving, proudly holding a keyed bagpipe led both of us (and everyone else who has since seen the image) to believe that Hale had been found. The instrument was a type of sordellina but certainly not of the fine quality of Settala’s as reconstructed by Marco Tomassi (see earlier in this edition). This bagpipe, with all its keys and extensions could certainly have played the hornpipe in the engraving.

Whilst the notes and writings of a number of Victorian antiquaries had done much to cement Hale’s fame by referencing him in several works, further detailed information about him was severely lacking. The absence of any defined first name or any concrete dates made further research very difficult. The only verifiable date we had was 1710-12, the period during which Sutton Nicholls, the engraver of the portrait and tune, was working from the address in London noted on the engraving.

I concluded my article with a series of questions which I hoped to answer in the future. So, where have I got with my research in the intervening 7 years? The answer is somewhere but nowhere.

Having re-read my article in preparation for this update, I realise that I was quite tentative in my conclusion that this was Hale the Piper. However, I am now much more confident in saying that I have no doubt that it is indeed him and he commissioned the portrait to proudly show off himself with his pipes. The style of the painting fixes it clearly to the late 17th/early 18th century, which ties in with the date of the engraving. Sadly, despite further research by the archivists at Calke Abbey, they have no idea how or when the portrait come to be there.

I believe that whilst Hale may have originated in Derbyshire, it was in London that he found his ‘fame’. His name may well have been made due to self-promotion and self-aggrandisement but he would not have been known at the ‘Derbyshire Piper’ if he had remained in his home county. So I focused my search on his assumed early days in Derbyshire and then his latter days in London. I started by following up on ‘findings’ by previous searchers of Hale.

An interest in Hale in the ‘90s and ‘00s led to various, unsubstantiated assumptions about him and a number of red herrings which needed to followed and tracked down. This included his appointment as ‘House Piper’ at Haddon Hall, a memorial to him in a church in near Holmfirth in Yorkshire, that his first name was John according to a reference to him held in Derby County Records Office and that the Records Office purportedly had other relevant documentation concerning Hale.

The claim about him being a piper at Haddon Hall seems to stem from the fact that there is a carving of a piper above the main gateway to the Hall, leading some to suggest that this is modelled on Hale. However, this carving dates from the early 16th century. Incidentally, there’s also another piper carving, dated mid/late 15th century at the rear of the Hall outside of the public gaze. Unlike in Scotland and the north of England, there is no tradition of House Pipers in English country houses. In fact, retained musicians are quite a rarity in English households in early modern England. Therefore, whilst a nice thought, the Haddon piper carving is not Hale and he would not have been a resident piper there.

Despite extensive searches by various people, no memorial to Hale the Piper has been found in any church (or for any other piper for that matter) in the area rumoured to have contained one.

Over the years, I have worked with two archivists at the Derby Records Office who have been very helpful in trying to unearth information on the elusive Mr Hale. They conclude that whilst a record card states ‘John Hale’ they can find no substantiation for that first name and have therefore assumed that it was a sloppy assignation from a previous employee dating from the mists of time. Their other records are simply printed references to Hale or piping in Derbyshire. This includes an article printed in the Derbyshire Times in January, 1931 about Hale the Piper. In order to illustrate the presence of bagpiping in the area it quotes from Edward Browne’s ‘Journal of a Tour of Derbyshire’ written in 1662 which states, “When we had viewed this famous town of Bakewell we returned to our inn to strengthen ourselves against what encounters we should meet next, where at our entrance we were accosted with the best music the place could afford, an excellent Bagpipes and Breakfast being ready I think our meat doined down our throats the merrylier, ….”. The article concludes by stating that Hale had travelled to London and was, “for a long time a great attraction at the famous old ‘Bartholomew Fair’, annually held at West Smithfield on St Bartholomew’s Day”. I have located another account of the district, written a year later in 1663, by Philip Kinder in his ‘Historie of Darby-shire’. In this he states, “the Peakeard & Moorlander are of the same ayre, they are given much to dance after ye bagg-pipes, almost every towne hath a bagg-piper in it.” It would be nice to think that the piper who so charmed and entertained Edward Browne at the inn was Hale! But it is interesting, all the same, to note that this area of England, piping was alive and well in the mid-17th century.

Someone else who has been researching Hale for a number of years is Bob Shatwell and he has extensively researched records on Bartholomew Fair and, whilst having uncovered many an interesting fact and anecdote, found no reference to Hale ever having been recorded as playing there.

With Bakewell being mentioned and Haddon Hall being close by, I liaised with staff at the Hall. In the Stewards’ Accounts dated 4th January 1670 is states ‘Given by my Hon’able lord & ladies command to Hales the pyper to stop him from pypinge (ie to retain him for piping) 2s6d.’ Hoorah! Finally, I had found a clear reference to Hale playing at the Hall, albeit only once and, frustratingly, no first name was given. (At this period there was no standardisation of spelling names, so Hale and Hales would have been interchangeable, Hailes, Haile, Hayles are also likely spellings.) I’ve gone through all of the Stewards’ Records and this is the only reference to Hale but there are other pipers and musicians brought in for specific occasions and lots of dancing too! By the mid-17th century Haddon Hall was no longer the main residence of the family, having moved to the much grander Belvoir Castle, so it was used for high days and holidays only. Interestingly, for Christmas 1670 another piper, Dickens, was also employed and he received two payments of 2s6d because, the record states, he piped for 5 or 6 hours in all.

Despite extensive searches in Derbyshire records, Bakewell Parish registers and even the efforts of my contacts within the Derby Archaeology Society, all further researches have drawn a blank and I’ve been unable to uncover any other reference to Hale in Derbyshire. Therefore, I turned my attention turned to London.

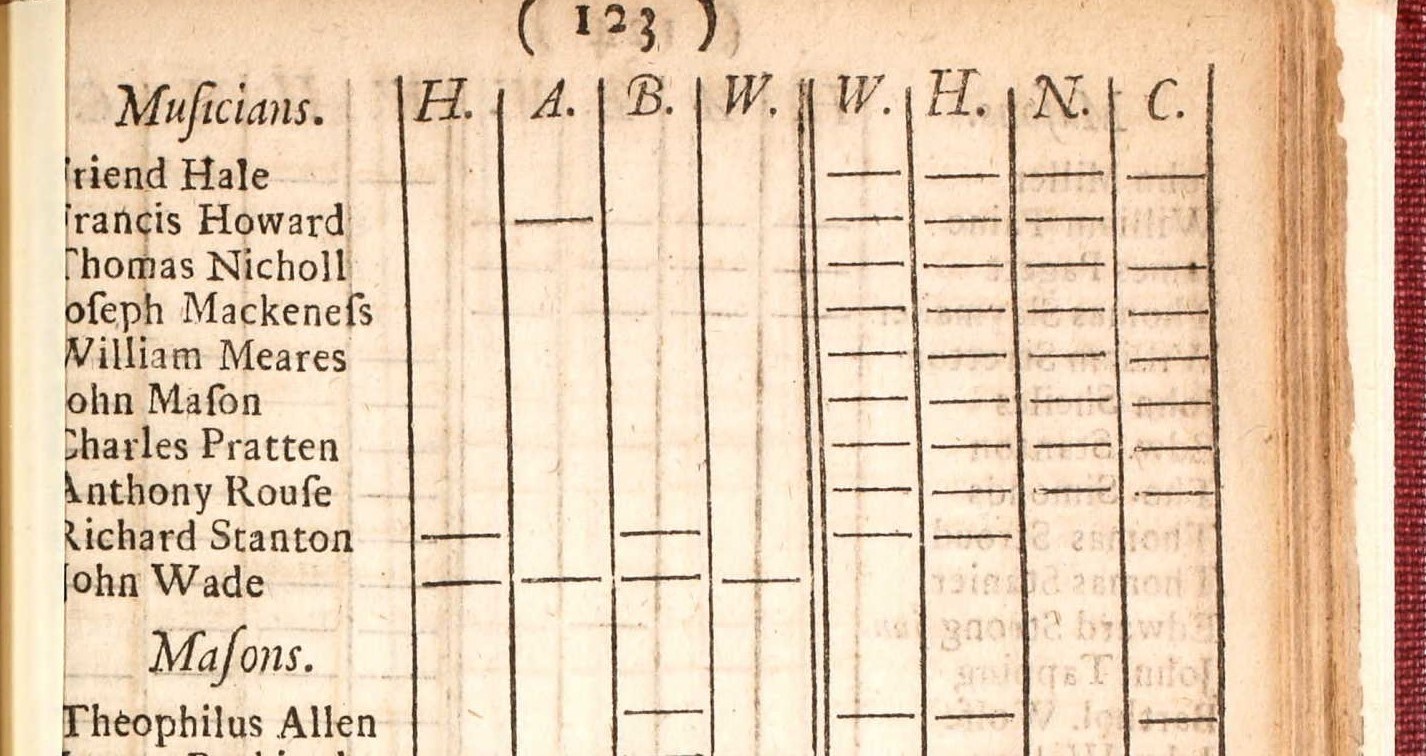

The parish register system of births, marriages and deaths was very patchy and often incomplete prior to 1837 when a formal nationwide system was introduced. So, the question was how to go about a search? I started with the two facts I had – the name, Hale and the profession, musician. I gathered this attribution was more likely than bagpiper. Bingo! In 1710 there was a general election and at that time there was no such thing as voting in secret and the London Poll Books still survive. All votes cast were recorded in a book, listing the name of the voter and who they voted for. Names were listed under the various livery companies and guilds operating in London at the time. There, listed under ‘musicians’ was the name Friend Hale. As an aside, it seems that the 1710 election was particularly controversial as there were accusations that the press exerted undue influence to ensure that all the Tories took all of the four available seats – does nothing change?!

Now with a forename, further investigation could commence and I enlisted the help of a friend of mine who is well versed in searching out family genealogy via Ancestry.com. First, we found the burial record of Friend Hale at St Saviour’s Church in Southwark in August 1724. (St Saviour’s and St Mary Overie Church became Southwark Cathedral in 1909.) Further digging revealed that Friend Hale was first married to Sarah. They had three children – a daughter Mary, born in 1696, then a son named Friend, who died soon after birth in 1702, and then another son, also named Friend, in 1705. It seems that not only did the second son not survive but that Sarah, the mother, likewise died at the same time. Hale married again, this time to someone called Hannah. They had 5 children – firstly a son in 1706, named Friend yet again, who this time lived until he was 42, then a daughter, Love Hale (1710 – 1720), then sons John, James and Samuel who all died shortly after birth.

Despite extensive search on Ancestry and various other parish records sites, we couldn’t find a birth record for a Friend Hale within Derbyshire, any neighbouring county or, indeed, anywhere in England within an appropriate timeframe. This was disappointing but not, in itself, surprising given the incomplete nature of records from this time. On finding the name Friend and the fact that a daughter was christened Love, my first thought was whether there was a Quaker connection. If so, this person would have been a very early adopter of the faith. However, on further investigation it seems that Friend, whilst unusual, was not an uncommon name in this period. In fact, another Friend Hale died in London in 1724 – in July, and this really did confuse things for a while.

Confirming that Friend Hale was indeed a musician, I found a reference to him in “A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800”. The entry states, “Hale, Friend fl. 1711, musician? William Mears and Friend Hale shared a benefit concert at the Town Hall at St Margaret’s Hill, Southwark, on 6 February 1711.” It is interesting that William Meares is a musician listed alongside Hale in the Poll Book of 1710. I can find no further record of Mears/Meares or what instrument he played. From the 1670s through to the 1750s benefit concerts were very popular and helped cement the concept of both public concerts and professional musicians. Very often, the concerts would be staged and marketed by the performers themselves and the money raised would go directly to the artists.

Well, that’s it and I can find no more despite going down various avenues and revisiting them from time to time over the last few years. Is Friend Hale the Famous Derbyshire Piper? I have no idea – but I would like to think he is! If it is Hale, then Friend would have been a young man when he played at Hadden Hall in 1670. Likewise, he must have married and had a family fairly late on in life. Guessing he would have been born c1650, that would put him as being in his early 70s when he died. However, these dates tie in with the approximate age of him as shown in his appearance in the portrait and engraving – in the region of late 50s/early 60s in 1710. Perhaps this is Friend Hale after all.

As to my other unanswered questions from seven years ago: assuming the dates are correct, the three monarchs Hale played in front of are most likely to be James II (1685-1688), William III (1689-1702) and Anne (1702-1714). However, Charles II and George I also fit the bill, so I’m still no clearer! How did Hale find out about the sordellina, an instrument not recorded as having been seen or played in England, how did he acquire the skills to make such an instrument (if, indeed, he actually did make them)? There are still many unanswered questions and therefore the quest continues.

An Acquaintance of Hale?

A number of years ago I was reading the excellent, and highly recommended, book ‘Music and Society in Early Modern England’ by Christopher Marsh (Cambridge University Press). Each page is full of interesting facts or references and it is also an immensely readable text. But one section made me literally jump out of my seat and got me very excited indeed. In referencing a speech, made sometime in the late 17th century, extolling musicians at the annual Minstrel’s Court at Tutbury in Staffordshire, the gentleman was quoted as saying “I dare say old Will Ward of Leeke (one of the top of your kin) with his melodious Large pipes & his son James with his violin are oftner & further sent for than any doctor or Chirugeone [surgeon] in the place where they live.” Now, this is interesting for several reasons. Firstly, it’s a nice description of pipes (pitched in low D or C?), it shows how the ‘old’ bagpipes of the father are played alongside the fashionable, ‘new’ violin of the son and it reinforces that in the past, as today, good music is an excellent medicine! But most of all for me – it mentions my home town of Leek.

There is a paucity of early civic and parish records in Leek as, according to a local historian friend, they were destroyed by a fire. However, thanks to research by Walter Woodfill (Musicians in English Society from Elizabeth to Charles I, Da Capo Press, 1953) I did know that Leek had at least one wait (civic musician) because records surviving in Coventry show payment made to a wait from Leek from 1639 through to 1711. (Coventry, being a major city, employed civic musicians from a widespread geographical area to play for various large-scale events held there. It is about 70 miles between the two locations, so a considerable journey to undertake in the 17th century.)

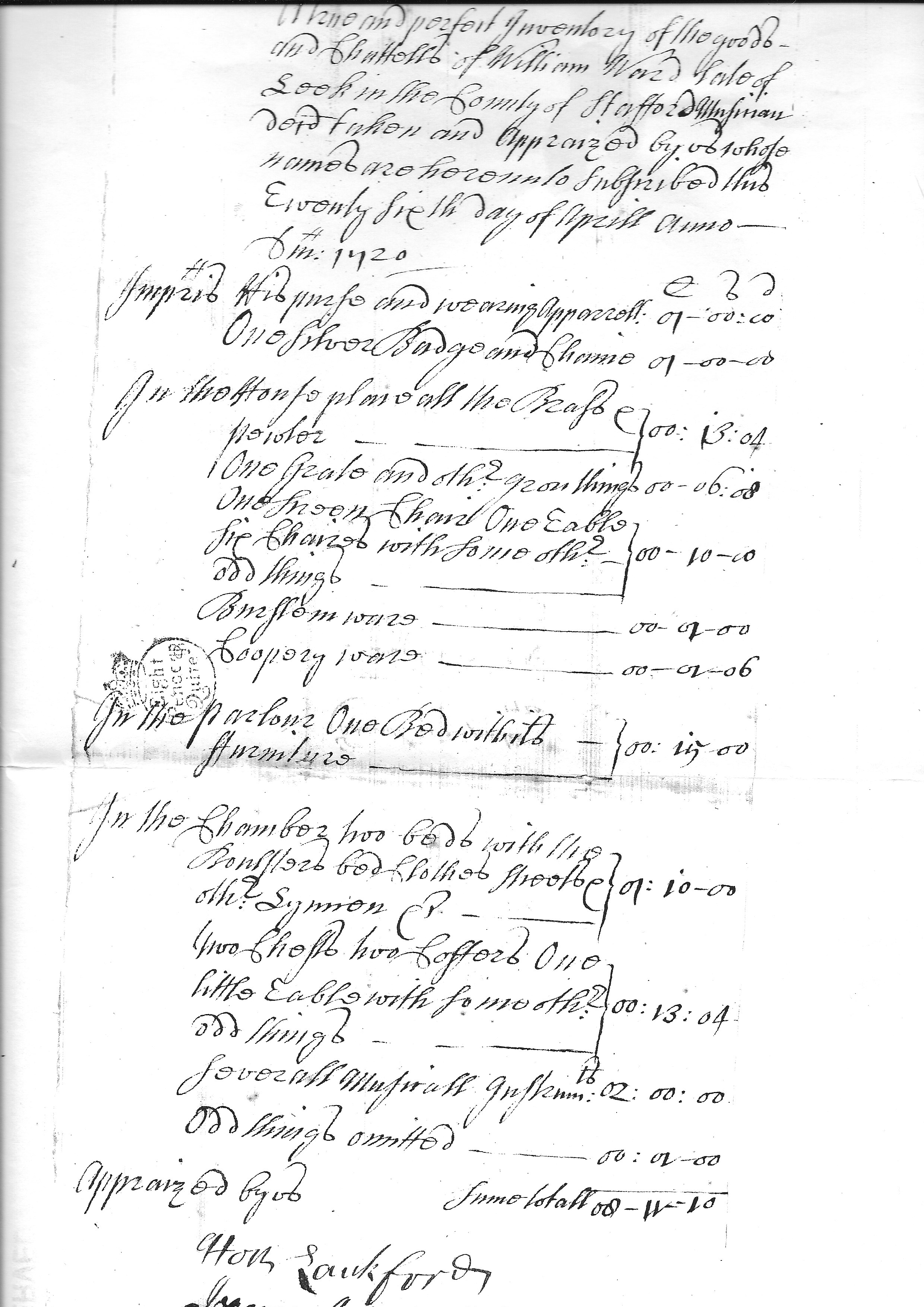

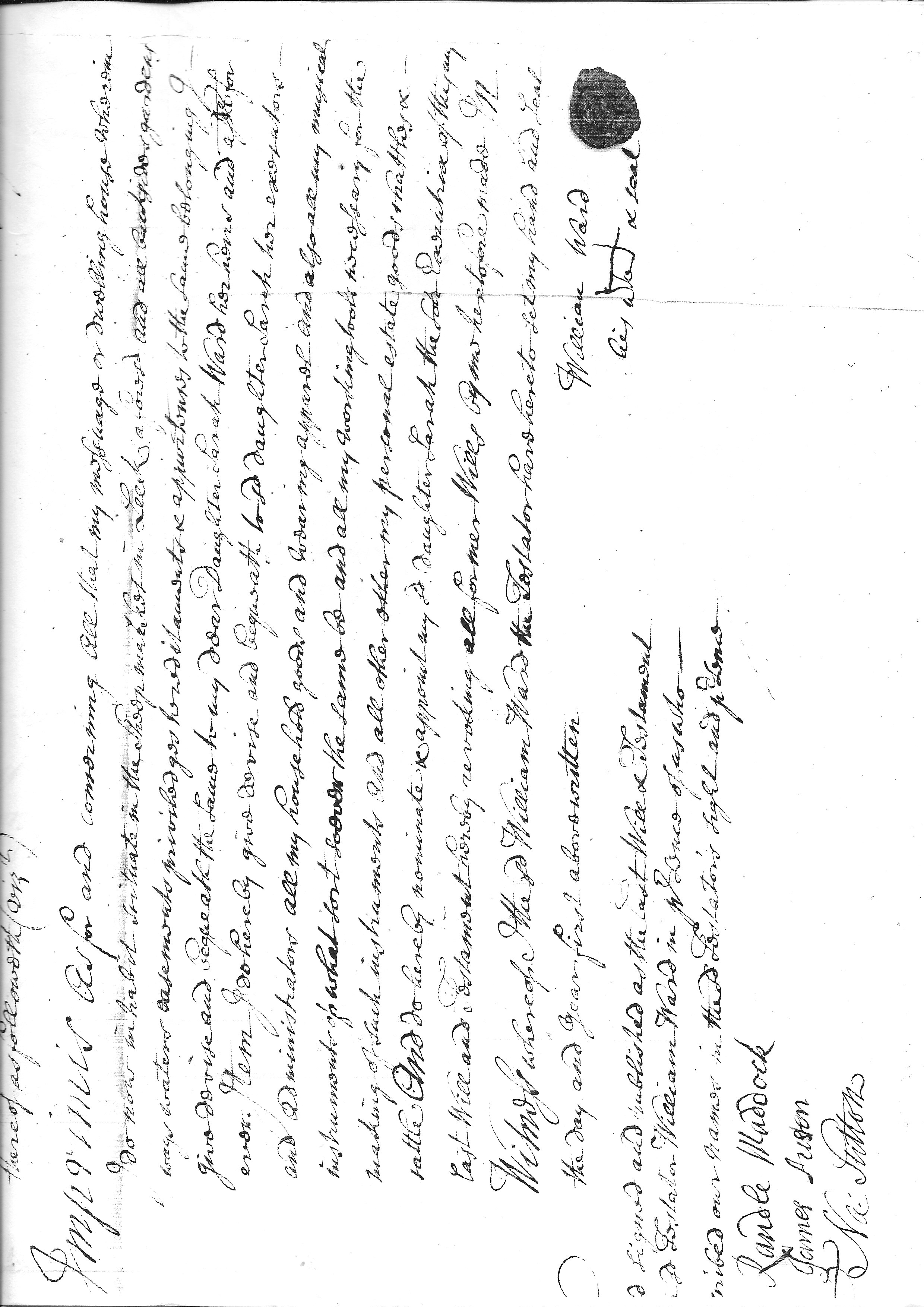

Through my historian friend, who had carried out in-depth survey of surviving Leek wills, I was able to track down the will and probate documents belonging to Will Ward which were now lodged in the Lichfield Record Office. It was with a certain amount of eager anticipation that Eric and I undid the envelope when the documents finally arrived with us. There was a will dated 30th June, 1716 and the probate inventory, taken after Ward’s death dated 26th April, 1720. We were, of course, looking for any references to Will Ward’s bagpipes but what we found was much more exciting than that!

The first paragraph contains the standard legal details found in all wills of the period. The second paragraph begins to be more specific with William leaving his house and belongings in Sheep Market to his ‘dear daughter Sara Ward’. It continues. “I do hereby give devise and bequeath to said daughter Sarah her executors and administrators all my household goods and wearing apparel and also all my musical instruments of what sort soever the same be and all my working tools necessary for the making of such instruments and all my personal estate goods chattels and cattle”. There it was, in black and white….not only had we found Will Ward, musician (sadly no specific reference to bagpipes) but he was an instrument maker (bagpipe maker?) too! Excitedly we turned to the probate document and Will Ward’s inventory. The key items listed were:

| His purse and wearing apparrall | 01 – 00.00 |

| One Silver badge and Chaine | 01 – 00.00 |

| Several musicall instruments | 02 – 00.00 |

What jumped out immediately was the value of his clothing (£1.00 when his china and cooking wares came to 2 shillings, and a table and chairs is 10 shillings.) and the listing of a silver badge and chain. Had we not only found a bagpiper, an instrument maker but an actual town wait as well?

Sadly, due to the lack of civic records in Leek this could not be substantiated. As the Tutbury quote was so specific in his praise of Will Ward’s bagpipe playing, Eric and I are pretty sure that even though bagpipes are not mentioned specifically in the will, the instruments in the will would certainly have included bagpipes. I spent several days in the library poring over records and I managed to find an earlier address, on the outskirts of the town, for Will Ward, together with the birth record of his son James, the violinist, and another son. What puzzled us was why, when Will had two sons, was the estate and instruments left to his daughter, especially when James was a musician and continued to be after his father’s death? This situation was clarified by my historian friend. It seems that many people had a farm or smallholding outside of the town and that was often the more valuable estate. These were often taken over and lived in by the son prior to the father’s death and therefore not mentioned in the will. It was only the lesser value items or dwelling houses that were specified and left to daughters or other family members. Even being told this by someone who had studied local wills in some detail, I still find this strange.

In poring over the parish records, I was very pleased to find an entry for another Leek bagpiper, John Clarke, who died in 1698. I also came across a reference to the burial of an infant in June 1707. The name of the child was Joseph Hales and he was named as living in Bakewell. This got my imagination churning. Could there have been a connection the Hales and the Wards? Did Hale and Ward collaborate on bagpipe making and bagpipe development? They were, after all, the same age, from the same geographical area and both players and makers of bagpipes. Was Joseph a relative of our friend Hale the Piper? Was Hale visiting his fellow bagpiper and instrument making friend in Leek when his son died and was therefore buried in Leek? Sheep Market, where Will Ward lived and worked, still exists today and is placed just off the old Market Place. At this period, houses weren’t numbered so I’m not sure which was his house but I often think of him when I’m doing my shopping in that street.

Finally! Sometimes I wish I was a better organised researcher than I am. When I come across references, collect notes and bits of paper all the time and do my best to file and notate them regarding their source, subject and so on but sometimes I simply don’t bother/intend to do it later/forget all about it/etc. In revisiting my folder on Will Ward in order to write this article, I found a photocopy of a page from a newspaper called The Derby Postman, which was published roughly twice a month between 1727 and 1731. I have absolutely no memory of how I acquired it – but it contains a fantastic piece of news from June 1730. The item reports on the celebrations staged by 68 year old George Cook, in a village near Wirksworth in Derbyshire. George held a feast and entertainment for 200 of his near neighbours to mark the birth of his son to his second wife, who just happened to be his god-daughter. Here are the highlights:

“….. being overjoy’d at the Success of his Nuptial Performances, gave an Invitation to his Neighbours to partake of a bountiful Entertainment, to compleat which, he brewed two Loads and a half of Malt last march to be ready against the Christening and this Week he provided One Hundred and Sixty Pound weight of Beef, Three Sheep, a Large Bull-Calf and a couple of Lambs, etc. He also ground a Quarter of Wheat into Flower for Pies and Puddings, the latter of which were as many in Number we are inform’d as he was Years of Age. ….. The Company being seated in Rank and File, the Dinner was usher’d in with the following comfort of Musick, viz Two Fiddles, a Hought-Boy, a Bassoon and Bagpipes; ….. The Dinner being ended, Honest George calls to the musick for a Derbyshire Horn-pipe, which was footed upon the Sod for their further Entertainment.”

There are interesting links between the accounts of George Cook and Hale – the bagpipes, the Derbyshire hornpipes and, if Friend Hale really is our man, he wasn’t the only elderly gentlemen having children!

All three of these accounts, Hale the Piper, Will Ward of Leek and George Cook’s christening entertainments are rooted in the late 17th/early 18th century, a time when it is supposed that English bagpiping has by and large disappeared and been replaced in popular culture by the violin. There is no doubt that the violin had taken prominence in this period but I feel encouraged to find that, in the north Midlands at least, bagpipe playing and bagpipe making are still part of everyday life. Perhaps the demise of the bagpipe by this time has been exaggerated?

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!