The Bagpipe Society

The Muzelsak - Muchosá Part 1

Ever since the revival of folk music started in Belgium, around 1965, and an "own" bagpipe emerged alongside the rommel-pots, hurdy gurdies and Lichtervelde accordions, we are troubled with the identity of the instrument. Still, our bagpipers are teased with lame jokes about wearing a kilt and whether or not to have underwear. And even, when players are approached by people showing genuine interest, the reference to the Celtic tradition still prevails and the conversation is introduced by their experiences of Scotland or Ireland.

Let me first point out that in Dutch we use the term doedelzak as a general collective term for all wind instruments with a bag and several pipes, with single or double reeds. The actual Dutch word doedelzak is in fact a loanword from German. The word dudelsack, also replaced the older sackpfeife there. The word became popular at the time when many Polish street musicians were active with their dudies. Before that, we usually spoke of muzelzak, moezelpype or cornamuse, all coming from Latin musa, but also the word quene is used occasionally. These names could indicate different types in use at the time in our regions, but it is not certain that this happened consequently.

In this article, I want to talk about the Muzelzak or Muchosá, the smaller type. This was launched in the Belgian Folk World in the 1970s, partly because of the attention the Hainaut Museum pieces received, but as folk evolved and folk instruments such as the hurdy-gurdy and the diatonic accordion became more popular, the Muzelzak was considered less practical and a bit forgotten because of its key in B flat. People started looking for an instrument with a key that could be used in ensemble playing. A bagpipe in G-C was developed by two instrument makers, Remy Dubois from Verviers in Belgium and Bernard Blanc from Vichy, France. For the French market, the new instrument was given the appearance of the French Cornemuse du Centre, with the small drone along the chanter and one drone on the shoulder; for the Flemish market, the model we know from paintings by Brueghel and his contemporaries was chosen. We call it Flemish bagpipe, Brueghel bagpipe or Renaissance bagpipe, but I would rather use the old name Cornamuse. No physical old examples of this model survive and one has to rely on paintings to recreate these instruments. This model became more popular from the 1980s onwards. However, the smaller muzelzak has an important advantage in terms of authenticity: we have, in fact, in the Brussels Museum of Musical Instruments (MIM) three copies that have been measured exactly, which makes the historical background of the copies more relevant. Lately, the muchosá or muzelzak is, once again, being mentioned. It is loved for its characteristic timbre. It is also extremely suitable for playing in marching bands. There are also historical reports of this. An account of the Dendermonde Ommegang of 1477 mentions a participation of 28 Muzelpypers.

Shepherds also played together in polyphony during their village festivals and pilgrimages. Yet it remains difficult today to convince players in our country to choose this instrument. Around 2000, the Galician gaita briefly became very popular with a number of followers. Then the commemoration of 100 years of World War I from 2014 to 2018 just brought Scottish bagpipes back into the spotlight, and new pipe bands have been formed in several places in our country.

But, we are going to talk about this particular small bagpipe, first described in the 17th century and given its own regional name depending on the region where it was played. In France, we speak of pipasseau (Picardy), or piposá (French Flanders and Artois), and in Belgium, of muchosá (Picardie Wallonne), and muzelzak (West, East, and Zeelandic Flanders).

Marin Mersenne

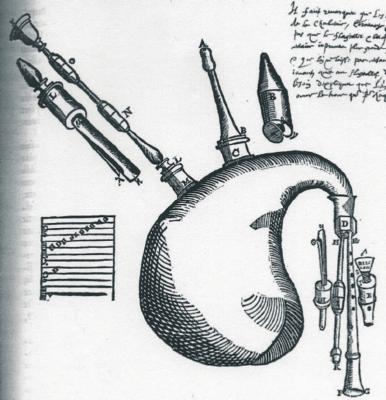

The Muzelzak is first described by Marin Mersenne in his Harmonie Universelle, published in 1636. The instrument is described in detail with the name cornemuse rurale des bergers with accompanying drawing. He distinguishes this instrument from other types of bagpipes he further describes, such as the Musette, the Italian Sourdeline and the Cornemuse de Poitou. On his drawing, Mersenne shows a mouth-blown instrument with a small drone next to the chanter and a large drone, which is held up on the shoulder. The chanter can be shortened by taking off the bell. The configuration is thus the same as that of our muzelzak or muchosá.

There are several French types known with a small drone next to the chanter such as the chabrette du Limousin, but on the chabrette the large drone is held sideways on the left forearm. Also, the cabrette from Auvergnes and the types of cornemuse du Centre, have a small drone alongside the chanter but these too differ just a little too much from the type described by Mersenne. The cabrette's small drone, is called chanterelle, and features a double reed instead of a single reed. In the Spanish Pyrenees, we have the Aragonese gaita de boto also with a small drone next to the chanter, but here too, the structural characteristics make it a different type of bagpipe. For the length of the chanter of the cornemuse des bergers, Mersenne gives ‘13 pouces’, = 13 inches. This corresponds to the length of our muchosá in B flat. As for the geographical distribution of the instrument, Marin Mersenne leaves the reader in the dark. But, based on the detailed description, we can assume that it is about the same instrument that we know in Belgium as muchosá or muzelzak and pipasseau or piposá in northern France.

Joost Verschuere Reynvaan

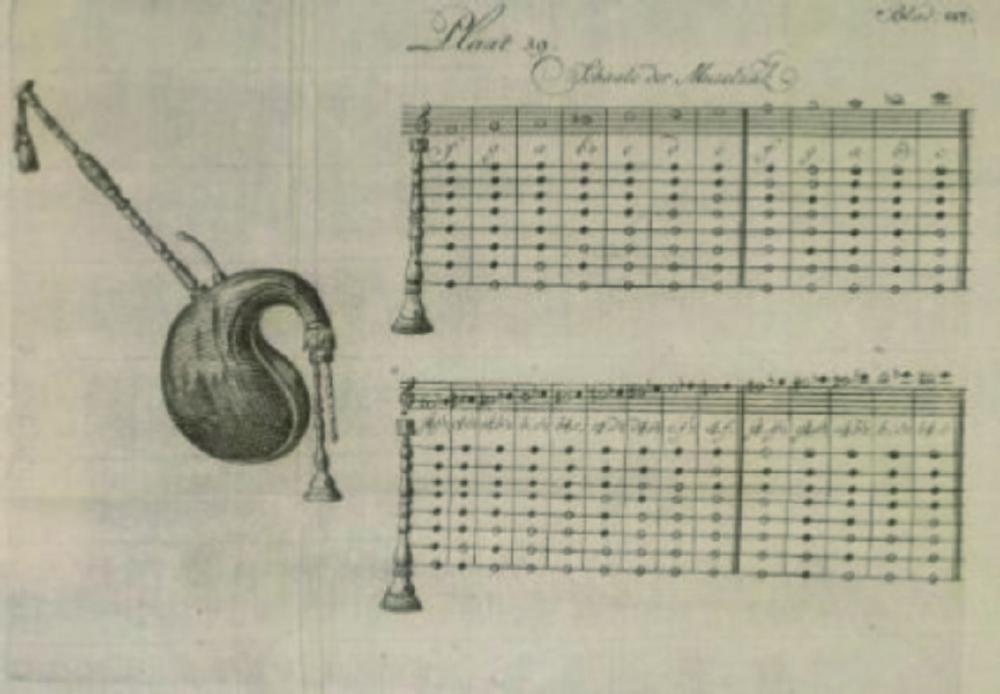

In 1795, the Muzykaal Kunstwoordenboek by Zeeland musicologist, Joost Verschuere Reynvaan, was published. In it, the name muzelzak is mentioned for the first time. The instrument is described in detail and the accompanying drawing concerns a bagpipe completely similar in shape and turnings to the Hainaut muchosas preserved in the Brussels Musical Instruments Museum (MIM).

Joost Verschuere Reynvaan describes in detail how the instrument works, giving a scale indicating that the instrument was in G-C, so with G as the root note and an F for the right hand little finger. Different, then, from what Mersenne specifies, for a chanter a length of 13 inches we think of the key as B flat. Is Verschuere Reynvaan giving a tonal scale here that could apply to several types of bagpipe? Possibly, many players used models in multiple keys and considered G to be the root note for every bagpipe they played, regardless of tuning. Just as today the clarinet player reads a do on the score, for a sounding B flat. Reynvaan describes two types of bagpipes, the Muzelzak and the Cornamuse, better known today as the Brueghel bagpipe. He makes a clear distinction, the Cornamuse has two pipes at the top, sometimes three and only one at the bottom. The muzelzak has only one pipe pointing upward, the large drone, which he calls the ‘grove roenker’. And below, two pipes, namely the chanter with seven finger holes and a thumb hole, with the small drone next to it. He also names the blowstick as the wind pipe, which is fitted with a valve. And he gives instructions on how to maintain the leather bag.

La Cornemuse Petyt

At the MUPOP museum in Montluçon, central France, there is a boxwood bagpipe that looks very much like our muzelzak. It matches the descriptions of Marin Mersenne and Joost Verschuere Reynvaan. The stock that holds the chanter and the small drone together bears a sculpted image of a bagpiper in 18th-century clogue. The finger holes on the chanter are all drilled with the same diameter drill and at equal distances between, exactly like the 3 muchosás in the Brussels Museum of Musical Instruments (MIM). The copy by Remy Dubois is tuned between a modern A and B flat, just a little bit lower than our own muchosás. It is still a guess where the instrument came from.

It was purchased at the ’ Marché au Puces’ in Paris in the late 1970s, by later antique dealer and musical instrument expert, Jean-Michel Rénard. The market vendor was also unable to tell where the instrument came from. More than likely, it is a Cornemuse Picarde, a Pipasseau from the Amiens region or a Piposá from the Béthune-Boulogne region. On both sides of the carved stock, there are inscriptions in bas-relief referring to the instrument maker and to the owner. One side reads FESIT PER ME (made by me) YOANNES STEPHANE PETYT and the other side APPARTIENb A (owned by) CHARLES PETIT # # 1782 #. That Charles Petit spelt his surname differently from the builder Stephane Petyt is a little bizarre, yet it seems obvious that Petyt and Petit were not necessarily two different families. The builder and the later owner may have been very closely related. Petyt was, in the 18th and 19th centuries, a surname that occurred almost exclusively in northern France and West Flanders. But all indications are that this is a French instrument. The back of the block is carved in the shape of two parallel cylinders and is somewhat reminiscent of a Parisian style like some models by bagpipe maker P. Gaillard.

The block is additionally richly decorated with butterfly bows, also in bas-relief, but these clearly show scratch marks indicating that the butterflies were actually originally lily motifs and were probably hastily updated into bows after the French Revolution, as the 'Fleur de Lys' was a reminder of the expelled French royalty.

Shepherd's Matins in Artois at Christmas time

A very picturesque and ancient custom was still in vogue at the beginning of the 19th century in Valhuon, a village in the North of France. At Christmas, during the midnight mass, when the time for the offering had arrived, the officiating priest, holding his paten, descended the steps of the altar and approached the balustrade in front of those present. Towards the ends of the balustrade, were two young men, each carrying a long branch of holly. At that very moment, the sound of the bagpipes, the piposó, as this musical instrument is called in the local dialect, was heard in the packed church, and a shepherd dressed in his usual costume, with a heavy sheepskin coat called ’ plu’ and a large felt hat, and holding in his hand his staff, to the top of which was attached a cake, was seen to be advancing towards the priest. This shepherd was followed by an individual, dressed in white from head to feet, with a white face, who was leading a beautiful lamb that bleated and resisted with all its legs not to follow him. Then came the shepherds from the whole region. When they arrived in front of the priest, each of them knelt down and kissed devoutly the paten which was presented to him. In turn, the shepherd offered his cake.

But when the children of the choir put their hands forward to take it, he pushed it aside so that they could not take it, and this game lasted for a while, to the great joy of the audience. At the end, the cakes were all passed to the priest, and the shepherds left, playing on their bagpipes the occasional tune. The tune used has, unfortunately, has not been collected and is now lost.

People liked to see the shepherds of Diéval arrive, whose outfit was magnificent: a large hat decorated with ribbons, white gaiters, fixed below the knees with pretty red and green bows, a helmet and breeches of hazelnut-coloured fabric. These shepherds walked majestically forward playing the most beautiful pastoral melodies. In Valhuon, the Shepherds' Matins took place for the last time on 24 December 1807. It is believed that the Matins did not end in Sombrin until 1830. But they existed in other places in the Artois and were, there, longer in honour. In Wierre-au-Bois, a kilometre from Samer, this custom was still practised in 1870. The shepherds from the neighbouring farms and villages, dressed in their sheepskin coats and their large waxed hats on their heads, came to midnight mass, each followed by a lamb and a dog, blowing their bagpipes.

When mass was over, they would go together to the Christmas manger and there they would play local Christmas songs, including the one that is still sung everywhere today: " Il est né le divin Enfant".

The Piposá’s of Rébreuve-Ranchicourt

During the restoration works of the Earl's Castle of Ranchicourt in 1995, one finds in a folder of drawings, a work from 1823, entitled 'Procession for Saint-27 Druon, patron saint of shepherds'. We see the polychromed statue of Saint-Druon, carried on shoulders, and further on, a statue of Saint-Mary with child. In the foreground, two bagpipers.

The instruments are painted with a few brushstrokes, yet we clearly recognise the details we know from the muzelzak type. The scene is set in northern France near Béthune, where this shepherd's instrument was known as piposá. In the corner of the painting is written Ph. d. R. 1823. These initials refere to Philibert d'Amiens, Count of Ranchicourt, 1781 - 1825. He lived in the Castle at Rébreuve-Ranchicourt in Artois, of which a barn is in the painting. This find is very important. It is the first-time iconographic evidence has surfaced of an existing bagpipe tradition in northern France. Until then, the piposá had only been mentioned now and again in archival texts. It was also linked to the worship of Saint-Druon by shepherds in this region, a cult that was also particularly strong in Belgium represented by the Confrérie de Saint-Druon. It is conjecture whether Artois shepherds had contact with Hainaut shepherds, but it is not impossible.

Shepherds were used to moving over long distances. Philibert d'Amiens, besides his noble duties, was a prolific painter. He won a number of medals with his works, including at Douai. Other works by him can be found on auction sites.

Unfortunately, the trace around the work with processional scene has been lost after the restoration works of the castle. The statue of Saint-Druon, which was still in the castle before the works, is said to be under restoration at the moment.

The Lobidel Stock

In Paris, at the Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires, there is a wooden block with a carved face. There are two cylindrically drilled holes and the piece of goatskin leather, tied to the block, is cut off from what was once a bagpipe. The artefact is a double stock, meant to hold together a chanter and a small drone, and was attached to a goatskin leather bag. Nothing is known of its provenance, but, carved parts of a bagpipe rather point towards Flanders and northern France. Moreover, it has a name carved into it, Lobidel. Research on this surname isolates a very small distribution area in the Bruay-en-Artois area.

This brings us very close to these two pipers, who played during the procession in Ranchicourt, barely 7 km. There is a possibility that Lobidel was

one of the players depicted on Philibert d'Amiens' canvas, or at least an acquaintance of them.

Pierre-François Muselet, (1835-1915) piposá player near Boulogne

I got to know Patrice Gilbert as a hurdy-gurdy player when we went dancing every month in Lille with a delegation from Bruges in the early 1980s. A key musician of the folk revival and a regular visitor to festivals where hurdy-gurdy and bagpipes made their timid appearance. He found out years later that he had a traditional bagpiper among his ancestors. His great-great-grandfather on his mother's side, Pierre François Muselet, turned out to have been active as a shepherd in the Boulogne area at the time, around 1860, and as befitted a shepherd of the time, he also played the bagpipes, piposá, as Patrice's great-aunt remembered it. His grandfather, on the other hand, called it a biniou.

This Breton term has recently become more widely used in French to refer to bagpipes. The instrument itself has disappeared but stories in Patrice's family confirm the practice of the piposá in the Boulonnais and its connection to the pastoral profession. Pierre-François Muselet was born in Equihen (then Outreau) on 23 November 1835. During his lifetime, he practised many trades, not consecutively, but simultaneously, depending on the season and the occasion.

He was a shepherd on a farm with sheep near the junction between Outreau and Le Portel. He could also shear sheep and offered his services on many farms, as far as the Liane. One day, on his way back from shearing, he even fell into the river. This anecdote was told in a sober tone that suggested our shepherd was not entirely sober. His main profession was shoemaker and he offered his services everywhere. He could also reupholster chairs and occasionally, in winter, went out to sea to fish herring. During 35 of the last years of his life, he also worked as a gravedigger. During the time he was a shepherd, he played piposá. He was known to have played during midnight mass with other shepherds. This must have been around 1860, the time he was a shepherd. In a tobacco shop-café on the Place d'Equihen, run by a certain Fourquet, Pierre-François Muselet would often go and play in exchange for a drink. This was not appreciated by his wife, so much so that one day, she got fed up with these drunks and pierced the pocket of his bagpipe so that the café visits would stop. She made him believe it had been a mouse that had made the hole. As a shoemaker, he could have repaired the leather sack, but he chose to stop playing to keep the peace.

To be continued in the next edition of Chanter.

Sources

- Harmonie Universelle, Marine Mersenne, 1636

- Muzijkaal Kunstwoordenboek, Joost Verschuere Reynvaan, 1795

- De Vriendschap in twijfel gebracht, Het Burgerwelzijn, 23 juni 1883 – Erfgoed Brugge Archives du Folk 59, Patrice Gilbert 1992

- Archives du Folk 59, Patrick Delaval, 1996

- Archives du Folk 59, Christian Declerck, 2014/2021

Special thanks to:

Dominique Vandamme, Olle Geris, Remy Dubois, Hubert Boone, Jean-Pierre Van Hees, Patrick Delaval, Jean-Michel Renard, Stef Boone, Jean-Marie Van Coppenolle, Alex Calmeyn, Martin Rusek.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!