The Bagpipe Society

Latvian Bagpipes: Dūdas (Somas Stabules)

This story is about Latvian bagpipes. Like elsewhere in the world, many Latvians believe that bagpipes are played mainly in Scotland, and that Latvian bagpipes must be some kind of Scottish bagpipe. They are surprised when they are told that bagpipes in Latvia have existed since the 16th century. The other aspect of the story is the revival of a tradition considered to be lost but revived by people enthusiastic about the pipes, the music and the culture.

Traditional Latvian bagpipes are single-reeded, consisting of a hide bag, one drone (although some types have two), one chanter and blowpipe. The bag is traditionally made from goat or sheep skin. The end of the chanter may have an addition of cow horn and the drone usually has a carved-out wooden bell that works as a resonator.

A hallmark of Latvian bagpipes is that the chanter is fixed in the ’leg' of the hide bag and the drone in the neck. Pipes are pitched mostly in D key, but some players also use pipes in G key. In older instruments, found in Latvian museums, the reeds are made of split cane used for both chanter and drone, but nowadays it is replaced with the cane strip tied to the wooden body.

There are various names are assigned to the bagpipes in Latvia, depending on the region or the context. These include:

- Stabules – Pipes (Flutes), Somas Stabules – Bagpipes from Soma = Bag

- Dūdas; possibly from Turkish düdük, other names being dūkas, dūka, dūciņas

- Kulenes (Kule = bag, sack)

- Dūdu spēlētājs = stabulnieks (Player of Bagpipes = Piper), also dūdinieks (literary form), dūdenieks, dūdnieks (Suiti dialect)

History

The Livonijas Hronika (Chronicle of Livonia) by Balthasar Rusovs, which covers the period to 1583, contains several references to the use of musical instruments in sixteenth-century Livonia, particularly to the large bagpipe, which was apparently well known in every village. Bagpipes vividly described as being played together in the chronicle. In later centuries, the similarity of Latvian and Estonian musical traditions, and particularly those of the bagpipes, is highlighted in at least one former part of Livonia, namely, Livland. In his 1777 essay about Livland and Estland, August Wilhelm Hupel writes: " The bagpipe is the most common—and presumably a very old—instrument for both peoples [Latvians and Estonians], which they make themselves and blow very rhythmically in two voices with a 13

lot of skill" . Johann Christoph Petri in his 1809 work Neueste Gemählde von Lief-und Ehstland and Johann Georg Kohl in his 1841 work Die deutsch-russischen Ostseeprovinzen adopt a very similar stance and refer to bagpipes as the favourite or perhaps even most beloved instrument of the Latvians and Estonians.

From the 18th century onwards, the playing of piping declined quite rapidly and this can be largely attributed to three factors, the first of which was legislation. From 1753 the use of bagpipes was limited to smaller fairs and on 15 December 1760 a new law was enacted where they were outlawed completely, with physical punishments for the player and a find of five roubles for the master.

The reasoning of the law was grounded on the basis that the unruliness of drunken non-German servants would tempt others to commit crimes. (The ruling classes of Latvia were descendants of the 12th century Germanic invaders. The native popular was henceforth considered inferior.) On 20 April 1765 this prohibition and punishments were reinforced and in 1773 a bagpipe player could still be fined three thalers. This perhaps shows the powers of bagpiping and how they were probably used in social settings where drink was consumed, causing ‘unbecoming’ behaviours.

The second factor in the decline of bagpiping was intolerance based on religious ethics and fervour, led by the Unity of the Brethren (Herrnhuter) in Vidzeme, in the eastern parts of Latvia. Secular, non religious music was considered unimportant and even undesirable and they actively discouraged its use by their congregations. On occasion, loud music had been played outside of churches much to the annoyance of the clergy. Joahims Brauns writes about the disappearance of many older musical instruments in the eighteenth century and, based on Rudolph Minzloff’s work Beiträge zur livländischen Sittengeschichte des 18. Jahrhunderts, which recalls the accounts in 1740 of von Ekesparre, a representative of the Brethren movement: “They completely destroyed their bagpipes, violins and harps”. Outside of the areas controlled by the Brethren, their influence was less which is why bagpipes survived much longer in the Kurzeme, in the west of the country.

The third factor in the bagpipe’s decline was, as elsewhere in Europe, the introduction of the violin and other instruments, such as the harmonica. The harmonica was often played alongside the violin to the extent that the combination overtook the use of bagpipes.

The first evidence of violins and violin playing dates to the turn of the seventeenth century, and by the eighteenth century the violin had become a beloved and popular instrument. "Now they dance to the violins, but before it was to the bagpipes" (Latviešu Avīzes, 1865) In the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century bagpipes could only be found in western Kurzeme, especially in its Catholic enclave known as the Suiti region, where the last recordings were made in the 1930s, around Alūksne in northern Vidzeme, in eastern Latgale, and around Ilūkste in southeast of Latvia.

The documentation of bagpipe music in Latvia is not particularly rich.

The composer and folklorist Andrejs Jurjāns, during his notable field work expedition in the summer of 1891, in Alšvanga (now - Alsunga) met with a piper whose instrument, unfortunately, was kept in a shed that was full of hay at that time and therefore, he explained, he could not demonstrate his playing (Raksti, Andrejs Jurjāns 1980 [1892]: 116). He also mentions a story about a performance of seven Suiti bagpipers and eight buck‑horn players in Liepāja (1860), where they greeted heir to the Russian throne Alexander II when he visited the region.

The composer and folklorist Emilis Melngailis recorded approximately fifteen bagpipe tunes in the 1920s and 1930s in western Kurzeme, but most of that material was written down from singing instead of directly from playing the instrument. Only one piece, played by Pēteris Šeflers, was recorded by Latvian Radio. His playing was also included in the first Latvian sound film Dzimtene sauc jeb Kāzas Alšvangā (Motherland is Calling or Wedding in Alšvanga), commissioned by the Ministry of Interior Affairs and produced in 1935.

Bagpipes began to be revived in Latvia in the late 20th century and in 1980 some restored Estonian bagpipes were used in a folk-group “Skandinieki”. A sound recording and film using these restored bagpipes soon followed and in 1988, a group of bagpipers participate at the opening concert of the International folklore festival “Baltica”. In the 1990s, activity continued with Māris Jansons and Eduards Klints beginning to start making modern reproductions of traditional instruments. A landmark recording “Bagpipes in Latvia” was made in 2000.

Today, the best known bagpipe maker in Latvia is considered Eduards Klints, but also Uldis Austriņš is building bagpipes based on traditional models.

There are also now appearing some pipes with double-reed chanters, mostly made by Māris Jansons but also by Martins Tiltnieks.

Within the western part of Latvia is the Suiti region. This is a Catholic

‘island’ in an otherwise Lutheran part of the country. The area was granted UNESCO status as a Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding in 2009.

This is an area with a strong history of bagpiping.

The oldest information we have on Suiti pipers is from the 19th century.

In the summer of 1860, when Alexander II of Russia, the heir of the Russian throne, visited Liepāja, where he was entertained with a performance in a pavilion. There were seven Suiti bagpipers and eight musicians playing goat horns.

As described above, by the end of the 19th century bagpipes were almost nowhere to be found in Latvia, other than in the Suiti region where the bagpiping tradition continued until the first third of the 20th century. There were several well known players.

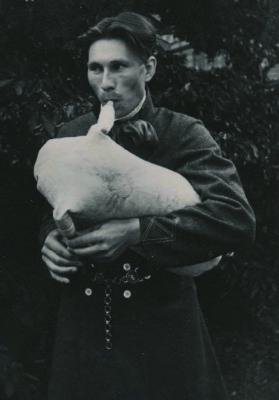

Pēteris Šeflers (born in Alšvanga on 9 August 1861, died 31 March 1945). A recoding was made of him playing in the 1930s and there was a brief excerpt of him playing for a wedding in the 1935 film, "Motherland is Calling or Wedding in Alšvanga". Video: //bit.ly/Chanter140

There are at least 5 other named bagpipe played living and playing well into the 20th century. This includes Nikolajs Heņķis, who was also a famous kokle player (a plucked stringed instrument from the psaltery/zither family). He was a carpenter and weaver and was born in Alsunga in 1864 and died in 1934. A follower of Heņķis was Jānis Poriķis. As well as being a bagpiper he was also a very skilfull player of the kokle, and having played in Stockholm in 1939, he donated his instruments, including his bagpipes to the Royal Museum in Stockholm. He died in 1992.

During the preparation of UNESCO application for heritage status, the Suiti community made an inventory of existing traditions and decided that the tradition of making and playing bagpipes had been lost. In 2013, a local Catholic priest, Andris Vasiļevskis, bought a bagpipe made by Latvian pipe maker, Eduards Klints, and gave it to the community to revive the tradition. Since then, the number has expanded and there are now about 13 people who play bagpipes in Alsunga. This is a small community of 1300 inhabitants and most of the local bagpipers are members of the folk-group “Suitu dūdenieki”. The group is very well‑known in Latvian folklore movement having participated in many festivals in Latvia and abroad, including the international folklore festival Baltica 2015, Baltica 2018, and Baltica 2022 (Suitu dūdenieki were invited to play the opening tune in both), several Latvian National Song and Dance festivals, Kaustinen folk music festival in Finland in 2019, and they also participated in the XXII International Bagpipe Festival in Strakonice (Czech Republic), where they performed together with friends from the folklore group "Abra" (2016).

Established by the folklore group Suitu dūdenieki, in Alsunga, every summer since 2018 there has been a meeting of Latvian bagpipers. This event helps to strengthen contacts between those wishing to continue in the tradition as well as promoting the traditional cultural values of the Suitu community. Another important task for Suiti community was to revive bagpipe making tradition. After participating in a bagpipe workshop in Drabeši in 2018, as head of “Suitu dūdenieki”, I have started building my own bagpipes for use in the folk group - where there is a constant need of maintenance and tuning of bagpipes!

What makes Suiti bagpipers different? I can't say our style is that different from other bagpipers in Latvia. However, only the famous Suiti bagpiper Pēteris Šeflers employed the very distinctive style of playing that we call elbowing today (you can see his style in a fragment of a movie). He elbowed the bag rhythmically as he played. The most important factor that highlights the tradition of Suitu bagpipes from others in Latvia is that our tradition was preserved for the longest time from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries into modern times. There are also many surviving tunes and melodies which were know were originally to be played on bagpipes.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!