The Bagpipe Society

That Irish Piping Pig Stamp

As a, perhaps notorious, defender of the proper interpretation of historical information, I felt compelled to comment on Chanter’s brief article about a bagpiping pig on an Irish postage stamp.1 I have no problem with $ean $tewart’s presentation, but I do find the text accompanying the stamp2 annoyingly naïve and potentially misleading to any reader who is unfamiliar with the real history of bagpipes. It would be equally wrong to call the bagpipe the pig is playing a Duda, Chimpoi, Tulum or GHBP. What the pig is playing is as much Uilleann as a bread roll is a wholemeal loaf or a daisy is a tree.

Inaccuracies and errors in the commentary accompanying the stamp are so b*****n’ obvious they can’t be ignored.

-

The pig, as $ean has recognised, like many other bagpiping pigs is a boar, signified his manly crest, which shows up better in another version of the stamp picture.4 He is playing a recognisable medieval-renaissance bagpipe, an interesting and quite well depicted illustration that does not require special interpretation.

-

The instrument has a conical chanter and two drones. I need hardly describe the so-different Uillean instrument, which the illustration does not depict – at all!

-

The bag is inflated with a blow-pipe, but bellows is an integral feature of the bagpipes called ‘Uilleann’. Indeed, the word ‘Uilleann’ is often translated as meaning ‘elbow’ in Gaelic, an obvious reference to the method of operating bellows, though it might also be a corruption of the name of its ancestral English-Scottish ‘Union’ Bagpipes. Probably, both interpretations are true. In the bagpipe context, ‘Uilleann’ seems to have a confection conjured from no tradition whatsoever (though sometimes erroneously considered to be traditional) by the early twentieth-century patriot and maker-up of bagpipe history William Grattan Flood.3

-

There are loads of bagpiping pigs. Indeed, there is another in this issue of Chanter (page 9) and I have sixteen in my picture collection, some resembling the Irish boar, who is often playing for dancing piglets, and some decidedly different.

Badge, Amsterdam 14thC

Misericord, Ripon 15thC

Misericord, Beverley 15thC

-

Do readers detect a striking similarity – apart from the Dutch drone deficit and prominent mentula – between the Irish pig and the Amsterdam pig, dated 1375-1450? I am not suggesting that the similarity has any particular significance.

-

At first, it seemed that, other than the location of the picture (in a document held at the Royal Irish Academy Library), it was going to be difficult find out more about the “16th century Irish manuscript”, so 16th century would have to do. It’s not unlikely, but more precise dating is desirable. My Googling led only to a tweet from the Royal Irish Academy Library about the stamp5 and an Irish philately site6 one page of which seems to have been the source of the stamp’s accompanying text quoted in Chanter.

-

So, I took a chance, looked for and found a facsimile of Bunting’s 1840 book7, which I had rashly pre-determined would probably be a Victorian red herring. But Bunting tells a lot more than I expected and his arguments – unlike a lot of stuff I have read by well-meaning but highly imaginative 19th century musicologists – seem quite plausible (pp. 58-59):

“That the bagpipe was also our proper military instrument in the fifteenth century appears from an account of those Irish who accompanied the army of King Edward to Calais,8 under the leading of the Prior of Kilmainham;9and we now proceed to give a specimen of the same instrument as known to the Irish about A.D. 1300. This ludicrous but curious illustration is from a manuscript of the Dinnseanchus,10 a collection of Irish history and topography, executed, according to Doctor O’Connor, about the above year.11 It forms part of an initial letter at the commencement of one of the chapters, and represents a pig gravely occupied in performing on the pipes, much in the same mode as the foregoing example.

“He presses the bag against his belly with the foreleg,

And from his lungs into the bag is blown

Supply of needful air to feed the growling drone,

which appears double, and ornamented with encircling straps, probably of brass. Four holes are represented open on the chanter, but whether the whole number intended be five or six, it is difficult to say. Certainly the instrument is not so complete as that of the Elizabethan period, but it is unquestionable that it had been known from time immemorial among the Irish, for in all the remaining poems of the Teach-Midchuarta12, varying in date from the tenth to the sixth century, constant mention is made of the cushlannaig13or bag-pipes.14The antiquity, therefore, of our old airs of the defective class can as little be impeached, on the ground of not having the bagpipe in early times, as can that of the more florid class on a similar objection to the antiquity of the harp.”

-

I strongly object to the judgement inherent in Bunting’s: “… our old airs of the defective class”, which is, I interpret, unpleasantly denigratory of bagpipe tunes. [e.g. “Golf is a game invented by the same people who think music comes out of a bagpipe.” – Lee Trevino.]

-

Why does the stamp’s text state, apparently without any trace of doubt, that the illustration is 16th century when the only well-argued source of information, Bunting, which the author cites, clearly considers it to be from around 1300? Did the author check Bunting or just copy the reference uncritically from another source?

-

Bunting concludes that: “Clearly the instrument is not so complete as that of the Elizabethan period”, and he has already suggested around 1300. So, was Bunting right about the date and is the author of the text accompanying the stamp, quoted in Chanter, who seems not to have bothered to check his information, completely wrong giving 16th century for the bagpiping pig?

-

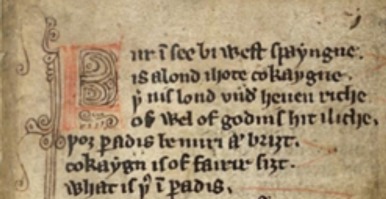

Does the text shown on the stamp (below, left) in fact look like 13-14th century Irish uncial script? If it does, we could more confidently date the bagpipe to a couple of centuries earlier than claimed, while agreeing with Bunting. As a guide, compare with the mid-14th century Kildare Poems example15 (below, right):

Having turned what was intended to be a quick observational note into a historical project, I’d better return to my reason to object to the Ireland Postal Service’s conclusion that the stamp design depicts “… the earliest known image of uilleann bagpipes”. (see 2. above) When I read the description, I thought (paraphrasing our editor’s similar response): “What the …?” How could anybody take an eye-catching historical image, presumably chosen because of its relevance and they do know it’s historical, then make no attempt to consider its historical context or even its appearance.

Whoever gave the final okay for this design – please let it not be Na Piobairí Uillean, who I hope are equally annoyed about this – seems not even to have looked at an Irish Uilleann bagpipe, made a quick comparison, and then applied some rudimentary critical thinking that would reveal the obvious differences. Aw c’mon. If anything, even to the untrained eye, the stamp pig’s instrument might more closely resemble the Scottish instrument.

The error doesn’t even deserve the excuse of careless ‘jumping to conclusions’, but I suppose we have to accept that that’s what people do – especially when it comes to bagpipes. A lot of folk just can’t ‘see’ what they are looking at or hearing. They ask: “And what is that?” and you reply (trying hard to make your necessarily blunt answer not seem impatient or sarcastic), “A bagpipe”. Then they express an astonished or even contradictory “No!”, and when they hear you play your medieval bagpipe or zampogna or gaita they decide (and indeed they might even tell you, sometimes quite belligerently) that it is Northumbrian. There was even one lady, who pointing at my friend’s hurdy-gurdy declared it to be a sackbut and she would not be persuaded otherwise.

1Chanter. 32:3, Autumn 2018, inside back cover.

3 The Story of the Bagpipe (1911).

5 http://bit.ly/Chanter57 http://bit.ly/Chanter58

6 Edward Bunting (1840). The Ancient Music of Ireland. vol. 3. Download at: http://bit.ly/Chanter59

7 Edward III. Siege of Calais, 1349.

8 Smith’s His. Cork, vol. ii. p. 43.

9 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dindsenchas

10 Rer. Hib. Script. Vet. Vol i. Proleg. 175.

12 Caution: as far as I can tell, cushlannaig seems to occur only in this work by Bunting. More research needed?

13 Petrie on the Antiquities of Tara Hill, Trans. R. I. A., vol. xviii.

14 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kildare_Poems

From Chanter Winter 2018.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!