The Bagpipe Society

The Subgalaic Gaitas

This article is written with the help and advice of Alberto Jambrina Leal, who has been researching, since the 1980s, the various bagpipes in the regions of: Sanabria, Carballeda and Aliste (N.W. Spain); as well as bagpipes (gaita) in the region of Trás-os-Montes (N.E. Portugal). This article will try and cover several gaitas in a geographical area, which has been divided due to national borders, but culturally are unified. To categorize these different gaitas from different regions that share common features, Alberto has used the term “Subgalaic” bagpipes, as he says this covers all the regions where these types of gaitas existed: (in Spain) Gaita Sanabresa, Gaita Alistana, Gaita Carballeda, Gaita Pedrazales, and from the province of León, Gaita La Cabrera; (in Portugal) from the village of Miranda do Douro, Gaita de Mirandesa.

I will focus on three gaitas (as this is what the author has come directly in contact with): Gaita Sanabresa, Gaita Alistana, and Gaita Pedrazales. What unites these bagpipes is the individuality of the playing style, their use of different modes (Dorian, Aeolian), as well as microtonal inflections in their division of tones and semitones.

My introduction to the genre of these Subgalaic gaitas was when I was playing in a concert in Zamora in 2013. I was introduced to Alberto Jambrina Leal a researcher and head of his traditional music school in Zamora. The gaiteros performing that night were from Alberto’s school and consisted of one gaita and one drummer, occasionally an ensemble performed, but the gaitas would play in unison, no harmonization was heard. These pipes are historically played with a drum or tambourine; due to their tunings it was difficult to harmonize with other instruments. These gaitas have not made the transition to the ‘Galician/Asturian’ type bands, with harmonized 2nd or 3rd part repertoires, but have kept their traditional format of drum and gaita.

These pipes were not mass produced; even today there is no pipe maker who produces them as a full time business. In the past these gaitas were from rural areas, piping in religious festivals, for marriages, social events or for enjoyment, singing accompanies the drum and pipes and often a piper would sing a line or two while playing the chanter, this would be difficult to achieve if the pressure in the bag was great. Some videos show the women playing the drum and singing while the men play the pipes. These pipes are loud, are made for the outdoors and a loud voice is needed to be heard. This adds energy to the performance; they were reportedly heard in the neighbouring village.

The villages were often remote, although not isolated from one another, they were separated enough to develop their own individual style. If a village had a piper he would play his style of music for dancing and social events, this would differ from another village in the area. The village of Pedrazales is to be found in the province of Sanabria and the gaita takes its name from that village. One family in the village has constructed this gaita; it holds many of the characteristics of the other Subgalaic gaitas, but the development of its tuning is unique to that family.

The Subgalaic gaitas have been going through a transition recently and are now being constructed and played in cities. This ‘coming together’ into an urban environment has posed many challenges to the music and instruments. This transition has happened with other pipes within northern Spain, and the change has been rapid, but with the ‘Subgalaic gaita’ the transition has not been collective; differences to tunings still occur.

The construction of these pipes can be classified as having one drone that sits horizontally over the player’s shoulder. The drone is tied into the leg of a goat (skin bag) and this lets the drone to fall over the shoulder instead of it sitting up in the air. Today synthetic bags are used, but the shape still allows for this position. The drone and blow pipe are attached to each other by a chord, positioning the blow pipe in a comfortable position for the players mouth. The drone has 3 segments, the end segment with a “bell end” (a hollowed out cavity). The neck of the goat is for the chanter stock. The blow pipe uses the other leg of the goat. The chanter and drones were commonly made from boxwood, but other woods are used today (Santa Palo, ebony).

The reeds are made from cane but plastic is used occasionally. The old reeds are wide and use a cane bridle; modern reeds look similar to Galician reeds but a bit wider. The reeds are often not made by the gaita maker, but are made separately.

The chanter is conically bored and has 9 notes. The majority of Subgalaic chanters resemble a tuning of a ‘minor key’. Historically this tuning existed in other pipes in northern Spain, but for one reason or another it has been replaced. Different pitches are to be found; mainly Bb and C.

I will use the ‘C’ for describing the types of modes used.

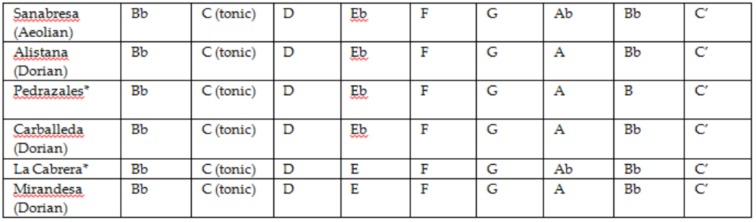

Subgalaic Chanters and relative modes in the pitch of C:

*Heptatonic Secunda Mode: Pedrazales (Melodic Ascending Minor); La Cabrera (Major Minor)

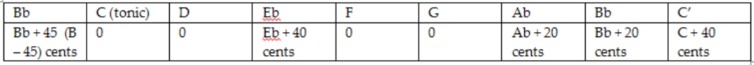

Alberto has presented 3 detailed readings of chanters using a Korg tuner (Alberto Jambrina Leal, 27.04.08)

The chanter of the Gaita Sanabresa in C of Luciano Perez, tested at 440Hz

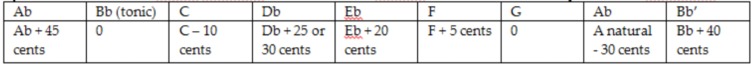

The chanter of the Gaita Alistana in Bb of Jordi Aixala, tested at 433 Hz by Alberto Jambrina Leal.

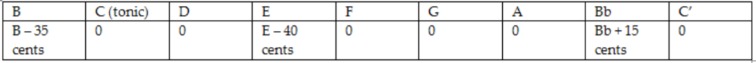

Alberto’s measurement of the (Portuguese) Mirandesa Gaita, pitched in C:

These examples show the diverse micro-tuning, which make it impossible to harmonize with other melody instruments, and yet these regions are relatively close together and share the same cultural musical environment.

None of the Subgalaic chanters play a 2nd octave, the thumb hole produces a top C’ (it is not a flea hole), so when a top C is played one lifts the thumb off the hole, as well as the rest of the fingers. I am not aware of cross fingering on these chanters to produce semitones. A player would use the same fingering on each of the chanters with one finger off at a time. I was also told that the bag pressure increases slightly as you go up the scale, the top C using a slightly higher bag pressure than the bottom C.

The Subgalaic gaitas are beginning to be tuned in a microtonal standardized system, with a tolerance interval of 20 cents. The positioning of the holes has never been based on harmonization. So the tunings have been different from village to village from piper to piper. 440c and the division of the octave was never an issue until recently, it was more to do with the harmonization of the note in relation to the drone. But now a systemization has been achieved due to the work done by Alberto, and bagpipe/reed makers making it possible to harmonize with other melodic instruments.

Another characteristic of these bagpipes are the intricate style of the ornamentation/gracing. Each note is approached by some form of ornamentation, trills, cuts, snaps etc. Vibrato is not only made by one finger playing a lower note, but by the whole palm flapping against the edge of the chanter. To a beginner the overall sound is a ‘mass of notes’, and if you were not familiar with the root melody it could seem overwhelming. If a 6/8 muñeria is being played, there is so much ornamentation that it can be difficult to tell where the melody begins, but this is its fascination of this music. There is something organic, something not “polished and over refined”, yet it is intricate, and needs study. Its attraction is in its micro-tuning and its colourful gracing. The accompanying drum forces a structure.

The best place to hear this, of course is in its live setting, a CD does not give it its true character. At an after-dinner party I attended, the tambourines and drums accompanied the players of the ‘Gaita Alistana’; each one playing their individual trills, vibrato etc., playing fast and loud, and above all of this the gaitero breaks off from blowing to sing, cutting through the gaita’s melody. Another musical event was Alberto playing the castanets, beating out a rhythm over a solo gaitero, his arms waving in the air; it is a visual performance as well as an oral one. In time, the gaitero was joined by others.

For the beginner, to buy a chanter can be difficult, not only deciding on the type of chanter but finding the right type of reed to fit. Often the pipe maker does not make reeds, this is done by a reed maker, and then the reed needs to be fitted and tuned to the chanter. I decided to buy a chanter online and I found a maker who advertised various chanters with various tunings. The problem was deciding which one to choose and what was popular. And it is not as easy as you think as these gaitas are played by different people for different reasons. I know of two music schools that play different types of chanters and in different keys. The Bb chanter was played in Madrid, and the C chanter was popular in the Alberto’s school in Zamora; in Madrid the Alistana chanter was played, and in Zamora a mix of the Alistana and Sanabrian chanters depending on the tune. In the end I chose a Bb for the Madrid group, as that was my home.

In the major cities in Spain you can find various “Casas Regionales” (regional houses) of the various regions of Spain, this is where the cultures of those regions represented within one building. Madrid has Casa de Galicia, Casa de Asturias and “Casa de Zamora” for the regions around the city of Zamora. As I live in Madrid these Casa’s have been a valuable source of gaita learning for particular regions. “Casa de Zamora” has a gaita band that had been playing under the musical leadership of José María Climent, the one of the founding members of the folk group La Musgaña; they adapted many melodies from the area of Castile and Leon, as well as Sanabria, Carballeda and Aliste into their repertoire.

Alberto and Climent had a different way of teaching and used a different repertoire to teach their students, not in competition with each other, but advancing the tradition in different directions. The chanter I decided to buy was the Pedrazales chanter, as I was told, by the maker, that it was used in the Madrid gaita band, but when I joined Casa de Zamora’s gaita group, Climent said they do not use it as a first choice, as it was not compatible with the majority of chanters in the ensemble. One of the first things Climent did when I showed him my chanter was to take a pen knife to the chanter reed, scraping it and cutting off the tip, bit by bit, until it was in tune with the other chanters. The top B note was taped over to make it a Bb.

The whole point of this was to make it playable within the group. A definite reversal of tradition from being an individualistic, solo village instrument, to become an ensemble, city instrument, compatible with 30 other Bb chanters; an ensemble environment compared to a duet of pipe and drum. Climent said if I had come to him sooner he would not have recommended this type of chanter, instead to buy a Bb Galician chanter (with Galician reeds) that are easily available and replaceable, and a standardized chanter that would play “in tune” with others. The minor scale would be easily achieved by simply taping over half of the D hole (3rd hole) to make it Db, thus obtaining a Pedrazales tuning, even though the Galician chanter has a B note below the tonic, instead of a Bb.

The emphasis was on keeping the tradition alive not by preserving it in its original village setting, but by adapting the tradition to a capital city and making it compatible for everyone to play together. No messing around trying to tune individual chanters, as the Galician’s had already achieved that with their chanters and chanter reeds. It was a case of using what was available to produce the sound. The majority of people were not regular musicians, and some had not played an instrument before, others were very good musicians and were well versed in a gaita tradition. Galician chanters are easily obtained in Madrid with little or no waiting time, Galician gaitas and reeds (also Gaita Sanabresa reeds) are bought there from “Tunumtunumba” music shop.

To achieve an overall sound, compromises needed to be made and in an ensemble this was the quickest way to do it. In the group there was a mixture of Pedrazales chanters, Alistan, Galician and Sanabresa chanters, adapted to produce an oval-all unified sound. The melodies played had been collected from the villages and been “simplified” for everyone to play, gracing was not marked on the music sheets, the key signature of the notation was with three or two flats depending on the region, (Alistana melodies using two flats, Sanabresa using three). An attempt had been made to unify the instrument for the sake of the band.

When I was there, Climent was producing a CD for “Casa de Zamora” featuring the gaita band. It was an ambitious work, often working with musicians who had never recorded before. The result was a beautiful CD including professional and amateur musicians, songs and instruments of that region. After the CD was made Climent left Casa, but the band still practices on a Wednesday evening about 8pm; if you are in Madrid they are very welcoming.

I had heard of other people who played music from Zamora, and I was told I could find them at the Plaza de Toros in Madrid on Sunday mornings about 11am. I went for a few Sundays, and again I found a different type of chanter, different tuning and a different maker, playing a different repertoire. There were only a few musicians, older men from the villages, who had moved to Madrid years ago; they did not go to Casa de Zamora either. They had their own way of doing things, they played in C instead of Bb. ‘C’ gaitas are the most common pitch in Spain, Bb is still used especially when singing; recently I bought a Gaita Sanabresa chanter in the pitch of C, made from ebony.

For me, these ‘Subgalaic gaitas’ are very different to the other pipes in northern Spain, as they have not achieved standardization to such an extent as the Asturian/Galician gaitas have. The playing style, its timbre, its musical interpretation is still individualistic, and not restricted to a harmonized “stylized” big band format. There are benefits to standardizing the pitch and tunings, and Alberto and Climent, are helping to promote these gaitas to a wider audience. There are pros and cons in standardization these gaitas, this often means preserving the instrument from extinction, but it can also mean ‘something’ gets lost along the way; the ‘Subgalaic gaitas’ have kept something of the originality and diverse characteristics of gaita playing in Spain, whether it loses its originality depends a lot how things evolve.

Further Information:

Alberto Jambrina Leal is Coordinator for the School of Folklore, a Musical Promotion Consortium, in the city of Zamora (Escuela de Folklore del Consorcio de Fomento Musical de Zamora). He is a researcher and performer. Alberto has been transcribing gaita music from his teachers: Serafín and Francisco Guillermo (Gaita Alistana); and Julio Prada (Gaita Sanabresa), “Tí Francisco” Baladrón (Gaita Carballeda); these transcriptions are used in his music school.

CDs

- Alberto Jambrina Leal, “Arbolito Florido” CD.

- Gaita Carballeda CD: “Rasgos, Ti Francisco, La Carballeda” (ethnographical recordings, booklet, notation)

- CD “Urzes, de urzes y madroños” Grupo de Casa de Zamora, Madrid.

- Selected La Musgaña CDs (featuring José María Climent former member of La Musgaña [1986-91])

- “El Diablo Cojuelo”

- “El Paso de la Estantigua”

Web sites:

- https://www.facebook.com/Jambrinamusic/

- Iberian Bagpipes in the UK, http://www.facebook.com/groups/632064580272868

- Los Gaiteros de Pedrazales, http://www.facebook.com/groups/129541473779255

- A collection of videos of Gaita: Sanabresa/Alistana/Pedrazales can be found at my YouTube site under “playlists” https://www.youtube.com/kevnsp/playlists

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!