The Bagpipe Society

My Gaita Journey - as a maker and player

Translated by Cassandre Balosso-Bardin

I started to play the bagpipes in the 1970s in Ferrol, Northern Galicia. It is relevant to recall the situation at the time: they are the inevitable circumstances that put my story in context. In the previous decade, Spain had abandoned autarky and the isolation policy that had defined the initial period after the war. It led to economic prosperity that influenced the social fabric, changed customs and encouraged the desire to change. The gaita, along with the Galician language, never ceased to represent the people’s most complete expression of belonging to a unique community, the Galician community. The instrument, maybe even more so than language, embodied this community’s emotional roots.

Thus, all bagpipers and nearly all of the artisan bagpipe makers were forced to take up other jobs and activities in order to make a living. Several musical associations, who had maintained the traditions during the precarious years of the dictatorship, had survived in the area of Ferrol as well as a few young pipers who had embarked on the task of refining the styles, modes, repertoires as well as attitudes of their musical forbearers. The four young musicians that we were, playing a formation of two gaitas, a tamboril (small drum) and a bombo (big bass drum), the canonical formation of the time, incorporated this movement, which dignified of the music, the role of the piper and the bagpipes in the tradition and the society of the moment.

Due to the fact that Ferrol was a military settlement, the town had several military bands whose musicians joined popular orchestras, took music exams and theory classes. Bagpipe music also included musicians who followed formal training and the case of maestro Bellón, the most influential figure in Ferrol’s bagpipe world in the second half of the 20th century, is a telling example. However, this symbiosis did not happen in other Galician regions where bagpipers were closer to a specific style and a manner of interpretation that were less scholarly (I use these terms with caution) and were embedded in oral tradition.

So, unto us, the young people, was thrust the mission of change, that we interpreted as the search for original authenticity, tarnished over the last decades by pieces that we judged inappropriate for the gaita, although these were played precisely to cater for the taste of an audience that, out of habit, asked for foreign tunes. We did away with the inclusion of saxophones, accordions, clarinets, snare drums as we deemed them inappropriate and unnecessary to play the melodies and harmonies of our folk tradition, we wanted something that was simpler, cleaner and, above all, more respectful towards the past and the source of this music. For more than 30 years, the core of the dominant strand of traditional Galician music was coherent with this vision and was over time established without any further discussions. I was fully active in this process.

During those years, the music of the gaita broadened its social role. To the usual accompaniment of choir music, dance and street processions in local festivities, we gradually increased its presence on stage thanks to the development of the instruments and to the incorporation of more complex music. The ability of new chanters to play chromatic scales allowed us to play new musical compositions that widened the limited scale of chords, inherent to more rudimentary instruments.

I followed this path, first with the Follas Novas quartet and then with the Raparigos de Ferrol. Both groups fit into what we thought was the simpler and more respectful way of playing traditional music. These were years where we participated in festivals, competitions, parish processions for patron saint celebrities known as alboradas (it was, and still is, inconceivable to imagine such a local celebration without the sound of the bagpipes and the bang of the firecrackers in the early morning hours), album recordings, recorded performances, the extension of the repertoire, rehearsals and so on. The second group, Raparigos de Ferrol, was Galicia’s most successful quartet in competitions open to traditional groups, winning many awards. We won these prizes with our own style based on a clear sound, clean and open with a solid technical basis, an intelligent interpretation of the traditional music repertoire originally written for a different instrumentation as well as controlled fingerings with impeccable ornamentation. This was a style that we could consider as being from Ferrol.

In the mid-1980s, after patiently mulling over the idea, I took a decision that was to be of great importance in my life: I left Bazán, a public service company, emblematic of my town where it was based, where I was an electrical engineer; I decided to dedicate myself entirely to the gaita. The first step for this new project was to participate in a bagpipe-making course with master maker José Seivane in Chao de Pousadoiro, a small village in one of the valleys of the Meira mountains on the banks of the Eo river, in the municipality of Ribeiras de Piquín in the Galician region of Lugo. Over the course of a year, I acquired the technical skills required for the instrument-making profession.

In 1989 I opened my own workshop, equipped with a lathe that had done many a job in Ferrol Vello, one of the original areas of my native town. With this lathe, I forged with tenacity and perseverance my own style as an artisan. I tried to maintain the links with tradition through aesthetic features and the design of the instruments, links that had been broken through the death of the bagpipe’s last artisans, rooted, albeit at times tenuously, in the region of Ferrol. The shape of the drones, especially the silhouette of the bell, which gives its personality to the drone or the pedal of the instrument, and the opening of the chanter are elements that I worked on, stylizing them in order to move away from the crudeness of the previous instruments.

Little by little, I created a personal sound through the combination of the conicity of the chanter’s bore, the diameter and the orientation of the holes, ergonomic considerations to facilitate the fingerings, the thickness of the chanter in order to achieve a specific vibration, the exterior aspect, the ornamentation… an unending path following research and perfection that has accompanied me to this day.

I never ceased to combine my work as a bagpipe maker with an ongoing activity including performances, teaching, sharing the knowledge about the instrument and participating in international events such as Saint Chartier, where I travelled to every year for the last three decades, seminars, symposiums with makers from other countries, concerts abroad… These are years of febrile and diverse activities, of teaching and learning, of accumulating experiences, of immersion in folklore and traditional music.

At the beginning of the 1990s, I went to a recorder-making workshop in Lostwithiel, Cornwall, with master Michael Ramsley. Knowledge of a technique that enables the creation of sound through something other than the vibration of two bamboo reeds, as is the case for the bagpipes, allowed me to broaden my skill set and I was able to start making instruments such as the pito gallego, a recorder with the range of the gaita’s melodic pipe, or the silbato, a whistle from ancient games. Every professional experience adds to and perfects the previous ones.

This was an intense period during which I diversified my instrument-making projects alongside my practice as a performer. It was a period, which, a few years later, led me to start an adventure that would open new horizons: the group Os Cempés. This was a group that, beyond its versatile instrumentation – bagpipes, recorders, clarinet, saxophone, accordion, bass, percussion and vocals – and beyond its evolving number of musicians, was a breath of fresh air for public performances, connecting with the audience’s emotional status and tuning in to their mental vibrations. The pleasure of interpreting catchy compositions was reinforced by the new joy of letting go of inhibition and creating space for improvisation. This style transcended the stage and captivated the enthusiasm of the audience; it was a magnificent and gratifying experience. These were years of expansive and fruitful creativity, also from the album production point of view. Os Cempés had for some years widened it repertoire with an informative session on popular dances that usually happened at the end of the concerts, an initiative that was well received by the public.

With Berros do Castro, a group with gaita, accordion, clarinet and percussion, and much like with Os Cempés in its last phase, I am commencing a research process, exploring the temporal space situated in the undefined sphere that can be found between memory and history. Songs that were asleep in the memories of our elders, distilled through the stimulus of paused conversations, hinting at melodies to stimulate remembrance. These are tunes which, in many cases, come from outside Galicia but that are, we now maintain, just as Galician as others because the Galician people consider them as theirs, integrated into their childhood and youthful memories. We are also plunging into lost archives of old popular bands. We look for tunes, songs, verses, many of them in a language that is between Galician and Castilian, with plebeian phonetics that are powerfully evocative.

At this moment in my journey as a musician, I find myself going down the path that, like many other young pipers in the 1970s and 1980s, I chose to leave behind. I am reviving a repertoire that, at the time, felt improper, illegitimate, colonizing and uniform, that put in danger the essence of Galician folklore. I am returning to the beginning and following the opposite path. Historical evolution has drawn a circle and I am once again engaged in the starting blocks but this time with a more generous and understanding vision, maybe less prejudiced and more able to give to each its authentic value. Thus I go on, without forgetting what I did, for there is no other way to explain what I am.

Listen online

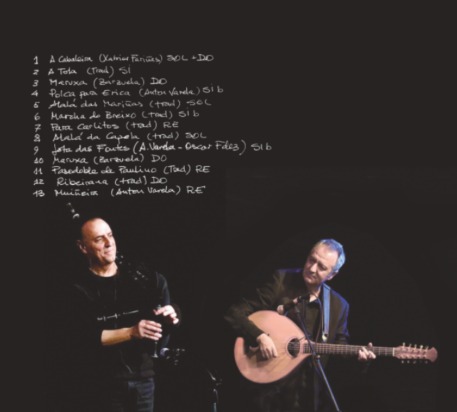

The cover from Anton’s latest CD with Carlos Beceiro (La Musgana) Anton has very kindly made three tracks available to Bagpipe Society members.

Also see YouTube recordings of this duo when they visited the Blowout in 2013 - on the Society’s channel. http://bit.ly/Chanter28

Polka para Erica

Jota das fontes

A Cabaleira

From Chanter Summer 2017.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!