The Bagpipe Society

The Revival of the Russian Bagpipe

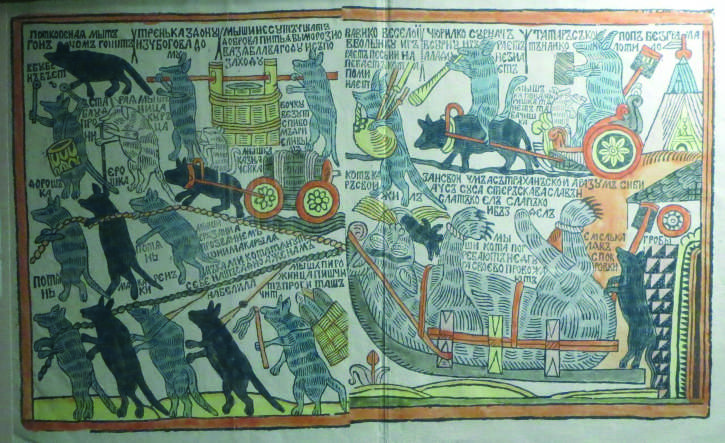

The Volynka bagpipe (from the word ‘vol’ meaning ‘ox’), valynka \pipe (duda) \goat (kozel) \bubble (puzir) was, until recently, an unexplored part of Russian instrumental music. However, it is also an unexplored spot on the map of European bagpipes. Whilst Russians know relatively little about bagpipes, there are several images of bagpipes in European and Russian travellers’ drawings, references in lists of musical instruments of the Russian Empire before the mid‐19th century, several images in folk pictures (lubock) and in church chronicles as well as references in literature and folklore. In recent years, the media has introduced new, previously unknown, sources.

The explosion of the diatonic accordion in Russia (where it is called a ‘harmonica’) in the early 19th century completely ousted the bagpipe from use. For the peasants of the central regions, the accordion appeared as an improved alternative to the bagpipe. The constructive idea of the accordion conceptually and actually is to move the playing mechanism directly to the air valve. The bellows of the accordion combines, in itself, the functions of both the valve and the bag simultaneously. At the same time, the system of the playing mechanism of the accordion, for folk musicians, was an absolutely natural extension of the closed fingering characteristic of most folk woodwind instruments of Eastern Europe.

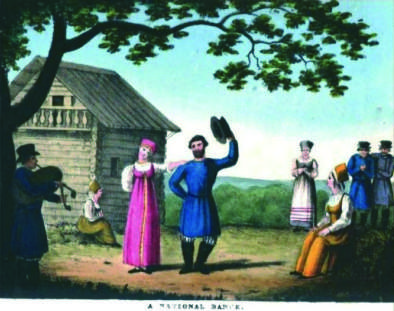

The accordion had the advantage of being more compact and less susceptible to changes in temperature and humidity. It initially replaced the bag- pipe for dancing and people began, instead, to dance to the accompaniment of the accordion. At about the same time, the ritual of processing or walking through a village to the accompaniment of accordion became popular.

This is another large layer of Russian folk music − music “for processing” (through the village, “na prohodku “). A separate genre is when the processions occur on saint’s days and festivals and in these instances, the accordion became used to accompany singing chants – “pripevki” (short, 4 line long songs). These same chants “pripevki“, were also performed but without processing, and were known as “four songs” (“pod pesni”). At wedding ceremonies and other special occasions it was the semi-professional musicians who usually played and received a fee for their performance, while at village processions, it was usually the young people who played.

Where there is a generic type of dance music that is played the same all across Russia, then it is called “Russian” (Russkogo). This music is typically based on two beats in a bar, played at different speeds depending on the context). Equally, there are songs which mostly use local folk tunes and which have an element of their local identity, (“we play this way”, “this is our local music”, “in other places they play differently”). In these instances, as well as from weddings and other celebrations, bagpipes were also ousted in favour of the accordion.

On the Russian-Belarusian border, the local traditions were much the same but the changes took place several decades later. In the late 19th century, bagpipers were still invited to play at weddings, to accompany old ritual wedding songs using the drone texture and a strong pentatonic “sound” and giving accompaniment for dance and entertainment. Thus, the accordion failed to adapt to the ritual songs.

The accordion took on part names from the bagpipe. On the Russian-Belarusian border, Hooke (Guk) is the name of the bagpipe’s bass drone and it also the name of the bass valve of the talyanka (ancient accordion) in the Pskov re- gion. Perebor is the name of the chanter of bag- pipe and accordion’s keyboard in Vologda, and in musical terminology perebor is the fingering combination corresponding to one bar of the tune.

Throughout the 19th century, the bagpipe could be found on the outskirts in the multi-ethnic regions. In the Vologda region, in the north of European Russia in the 20th century, the ancient one- row accordion “talyanka” was called “volynka” (bagpipe). Old people recount that even in the 1930’s, in some areas of the Northwest, there were still people who occasionally could be found playing a bagpipe. The longest surviving use of bagpipes was on the outskirts of Russia, in the East European Plain. Here, professional shepherds and boatmen would travel up and down the navigable rivers herding and breeding cattle. These people still used bagpipes in various festivals such as Christmas and Easter.

As soon as it goes out of fashion, a musical instrument is very quickly forgotten. So its meaning, appearance and how to play it disappears. However one finds that the name remains in the national culture. So nowadays, the word “bagpipe” or “dudar” can be found in folk songs, children’s games, and not only in children’s games (there is a game “Dudar” (Bagpiper) and a song “Play my bagpipe”) but what it means – nobody knows. Historical memory has erased all the details, leaving only the word.

The bagpipe didn’t disappear without a trace but it seems to have been separated into pieces. For large celebrations they started to use the accordion while the chanter or pipe (rozhock), remained as an independent instrument (the pipe always existed alongside the bagpipe), played by professional musicians. Shepherds continued to use the pipe as a calling or signalling instrument, but also used it for entertaining with friends. So, during the 19th century, instrument makers competed in the development and improvement of accordions, while the shepherds competed in the playing of pipes and hornpipes. They continued with this because they could still earn extra money by their playing.

We can certainly say that, in Russia, there were as many types of bagpipes in the 19th century as there were pastoral horns in the 20th century (and there is iconographic evidence to support this). There were many different types of horns, but two main types were the most popular: Either a double bore, made from cane, with six holes with or without bell – (pishiki), or a single bore- made from wood with five holes and a bell made of horn or birch bark. There were several local and regional combinations of these basic ideas. These two core types coincide, very naturally, with the bagpipes’ map of Eastern Europe. Pishchiki is an analogy of double chanter, single reed, no drone bagpipes of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea (chiboni) up to the Volga region (shuvyr). At the same time, the 5 holed, single bored instrument with a bell plus drone and sometimes an embroidered bag, fills the gap between the European Central bagpipes “dudas” (kozlami) and the bagpipes of Chuvash, Besermyan and Udmurts in the Volga and Ural regions.

At present, in Russia bagpipes are being developed again. These typically have a single bore, a drone, a horn bell and a goatskin bag. They use a range of scales based on a five hole or six hole fingering system, some have some extra holes at the bottom for the little fin- ger and a hole at the back for the thumb. There are also experiments with double chanter instruments using ox leather for the bag. It is this which originally gave the common name to the instrument – “volynka” – from “vol” meaning ox). After a hundred years of being in ‘retirement’, Russian folk music has developed and so the bagpipes have needed to develop as well – there has been a stabilizing and expanding of the scales of tunes and instruments. This is also illustrated in developments of the balalaika and the gusli. The range of notes available has expanded from 6 or 7 to 9 − 12 on the diatonic scale. Closed fingering systems and using the bell to amplify the lower sounds have allowed latent second voice polyphony, which is one of the specific features of Russian folk music. The trick is in the closed fingering which allows the two melodic lines, which in combination with appoggiatura melizmatika, gives the sound an authentic texture. Thought has also been put into ergonomics of the instrument to allow for high speed playing, over long periods, which is necessary for accompanying the dances. As pastoral instruments, single reed bagpipes have not undergone improvements and they usually have an unstable scale, just on the edge between pentatonic and early, not yet tempered, diatonic. On the horns, harmony colour is achieved through intonation and breath. Because of the requirements of today’s musicians, modern makers are producing scales which reflect the local instrumental tradition.

In Russia, bagpipes died out in the 19th century, leaving the space for accordions to take over. However, the music that was played on them lived through to the 20th and, in some places, even to the 21th century. The traditional music that had been played on bagpipes was adapted for the accordion and consequently then recorded by collectors in the second half of the 20th century. In addition, the reconstruction and restoration of Russian bagpipes which is taking place today is being based on the ethnography of an instrument designed to perform certain specific genres and styles music from 150 years ago. The bagpipe movement in Russia is only just emerging, however, this process is irreversible! Instruments are being produced and musicians are performing the music, so the instrument will live, grow and take its place in the great bagpipe family.

A YouTube channel, dedicated to Russian bagpipes where you can find a great collection of videos.

http://www.youtube.com/user/communitySKM

For further information on Vasily’s instruments http://rusbagpipe.ru/

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!