The Bagpipe Society

Pipes and Pipers: Galician Symbols of Ever Evolving Meaning

‘You must sing, / sweet piper girl, / you must sing, / for I’m dying from grief. / […] / To the sound of the pipes, / to the sound of the tambourine, / I ask you to sing, / dark-haired girl.’

From Cantares Gallegos [Galician Songs] (1863) by Rosalía de Castro (Translated by John Rutherford)

This article offers an overview of the tension between tradition and innovation in the world of the Galician gaita in modern times with the aim of showing the vitality of the gaita and the bagpiper as symbols of ever evolving meaning. To do so, we must start looking at the age of nationalism. Spain was no exception to the national movements that swept through Europe in the nineteenth century. In several Spanish regions, two competing national movements developed: that of the nation-state (Spain) and that of the region. Today, most people only think of the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia, but there were others, such as the piping region of Asturias, whose most well-known symbol is the cider El gaitero. Most of these regional movements found the spirit of the people in rural culture. Instruments associated with this culture, such as the gaita and the hurdy-gurdy, were revitalised and promoted. In the article ‘Bagpipes and Digital Music: the Re-Mixing of the Galician Identity’, the writer Xelís de Toro explains how the gaita, made of wood and textiles, and the bagpiper, a member of the rural community, ‘could represent perfectly the realm of the rural, nature and landscape, the places where Galician identity was to be found’.

It must be noted that the gaita (and the hurdy-gurdy, for that matter) is not only a rural instrument of the lower classes. Its first representations are found in the medieval manuscripts of the Cantigas de Santa María [Songs of Holy Mary], dating from the thirteenth century, and there are references to duets of gaiteiro and tamboril [drummer] being hired by all sort of civil and religious institutions from the sixteenth century onwards. According to the musicologist Casto Sampedro, these duets were intermediaries between the popular and the educated classes—they helped to popularise learned compositions.

Another key element of the Galician political project was the language. Galician (or Galego), a Romance language in its own right, but which many have considered a Spanish dialect, was revitalised. Traditional songs were collected and writing in the language was promoted. Examples of the relationship between the pipes and the language can be found in two foundational books of the Galician regional movement. The first book ever published (partially) in Galician, A gaita gallega [The Galician Pipes] (1853), written by Xoán Manuel Pintos, is a collection of poems heralding a new age for the language where the protagonists are an old gaiteiro and a young tamborileiro [drummer]. The image of the bagpiper as an old, wise man is a common one. A characteristic poem from the collection says: ‘Please God these well-played Pipes / bring memories to the good Piper, / and may thousand more men, / where the first one played, / also come to play the beloved Pipes.’ In this call to arms, ‘playing the beloved Pipes’ also stand for using the language and for promoting Galician culture.

Other examples can be found in the most famous Galician book of all times, the poetry collection, Cantares gallegos (1863), by Rosalía de Castro, the foundational writer of Galician literature and of the national movement called O Rexurdimento [The Revival], an oddity among the ranks of foundational writers of national literatures, who are overwhelmingly male. Two characteristic poems are ‘A gaita gallega’ [The Galician Pipes], a political poem lamenting the dire economic situation of Galicia, in which the gaita is said to weep not to sing, and ‘Un repoludo gaiteiro’ [A Dashing Piper], which introduces the well-known image of the bagpiper as a Don Juan. The male soloist, the piper, has long embodied elements of traditional hegemonic masculinities, especially heterosexual prowess. In fact, gaita is a slang word for ‘penis’. The double entendre between the instrument and the body part is present in a common proverb that celebrates the luck of the bagpiper’s wife: ‘A muller do gaiteiriño, muller de moita fortuna, ela toca dúas gaitas. Outras non tocan ningunha’ [The bagpiper’s wife is a lucky woman, she plays two sets of pipes. Others don’t play any]. He also became the hero of the popular classes. The image of the piper generated by Galician nationalism in the nineteenth century is therefore an interplay of notions of nation, class and gender.

It is common to assume that until recently all bagpipers were male but this is far from the case. In the opening poem of Cantares, which frames the book and also the Revival, the poetic voice addresses a ‘meniña gaiteira’ [a girl piper] asking her to sing and make merry. This girl stands for the Galician community and also for the female author of the book. One of the first female historical pipers we know of is Áurea García of Os maravillas de Cartelle [The Wondrous Ones from Cartelle], born in 1897. Since then, Galicia has singled itself out by its large number of female bagpipers when compared to other piping nations. Some elements that may have encouraged the presence of female pipers are the idea that the gaita and the bagpiper are associated with the Celtic world and therefore with lyricism, a trait widely considered feminine. They were also practical: the instrument was played during rural and communal work such as the flax harvest, often done by women. And, last but not least, quartets (two bagpipes, side and bass drum) were often family businesses and in a society where many men emigrated, women took over their roles.

Another crucial element of Galician nationalism was that of Galicia’s alleged Celtic roots. Inspired in the discourses of the Celtic Revival, the thinkers of the Rexurdimento argued that Galicia was a Celtic nation culturally closer to Brittany, Ireland, Scotland and Wales than to Castile, a Mediterranean nation. In Galicia, A Sentimental Nation: Gender, Culture and Politics (2015), Helena Miguélez-Carballeira explains how the trope of the sentimental nation ‘has helped sustain the unequal power relation between Galicia and the Spanish state’. The overuse of adjectives such as ‘nostalgic’, ‘sentimental’ and ‘longing‘ to describe gaita music have their origins in the Celtic discourse, but it was greatly helped by socio-economic circumstances.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Galicia experienced a period of mass migration towards Central and South America. For the gaita and the bagpipers, it meant a new world full of opportunities. The quartets, the most common formation at the time, organised their first international tours and gaita music was recorded for the first time. As a result of this mobility, twentieth-century Galician popular music incorporated Latin American rhythms such as habanera and rumba. The acute experience of migration has made bagpipes and their music closely associated with the idea of home and to the feeling of nostalgia for the homeland, called morriña. Another image of the bagpiper is thus as a figure who evokes the far-away home.

Since the fin de siècle the bagpiper was displaced from centre stage and, as happened in other European contexts, by the 1920s they were either subsumed within larger formations or replaced by bands which played other types of music. Two political events of great significance contributed to the slow decline of the bagpipe as a traditional instrument that was adapting to the new times. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and Franco’s Dictatorship (1939-1975) had a great impact on the instrument and how it was played. Although the régime fought against the Basque, Catalan, and Galician national movements, it was interested in the promotion of regional dance and music from a folkloric point of view and ‘bagpipes were included in the official Francoist culture as a means to incorporate an ambiguous and undefined Galician identity which posed no threat to Spanish hegemony’, as Xelís de Toro says. It was during this time that the design of the cover incorporated the colours of the Spanish flag (red and yellow). Despite their presence, the gaita and the bagpiper lost their status and prestige.

During the Dictatorship, there were initiatives to preserve folk music. The relentless work of Faustino Santalices, a bagpiper and a key figure in reviving the hurdy-gurdy, materialised in the foundation in 1951 of an influential workshop and school of Galician instruments. Groups and societies mainly devoted to singing and dancing were also crucial. Women played a vital role in these groups and the first female pipe band in Galicia dates from these years: the Grupo Saudade [nostalgia], active between 1961 and 1966. The bagpipe also adapted to the new times. A timid mass production and the use of new materials were behind a crucial structural change: the bag was no longer made from goat’s skin but from a cheap synthetic material. After several years, it was obvious to everyone that other materials needed to be found. Among their many contributions to the world of piping making, Antón Corral and Xosé Seivane, two fundamental names in the history of Galician folk music, made great efforts to make tempered gaitas and to broaden the range of keys. Symbolically many bagpipers starting holding the instrument differently: instead of putting the bass drone over the shoulder looking up, they put it completely horizontal to the ground, in a less conspicuous form. The bagpipes quartets continued livening up the popular festas but they no longer appeared in the posters under their own name but under the generic grupo de gaitas [bagpipe band] and they became the supporting act.

There were bands and groups who succeeded in maintaining the dignity of traditional Galician music and transmitting it to new generations who had to take over that responsibility in the years of transition to Democracy, from 1975 onwards, but it was far from easy to reconcile the ideas about the bagpipe as an instrument from the past with those that associated it with the promotion of folk music by Franco’s régime. Nando Casal and Xosé Ferreirós, the bagpipers from Milladoiro, a key band in the Galician Folk Revival of the late 1970s and early 1980s, alluded to the different meanings of the traditional bagpiper when they said: ‘we were on dangerous ground, we were people who also fought for freedom, politically committed, but who also wore the traditional bagpiper dress, which was seen as folkloric in the worst meaning of the word, and many liberals were not able to understand our role’.

The gaita has been a common presence at institutional events since the sixteenth century but, since the creation of the autonomous government in the early 1980s, it has become a contested political symbol at the inauguration days of the President of the Galician government. The tunes played are always the same, the March of the Old Kingdom of Galicia, the Galician Anthem and Muiñeira of Ponte Sampaio, being among the most important, but the number of pipers and their formation are political statements. In 1990, at the first inauguration of the conservative Manuel Fraga Iribarne, there were 1,500 pipers and, in 2001, after 11 years in power, there were 6,000, some of them from the Diaspora. The following president, from the socialist party, promised to avoid such extravagant statements and organised an inauguration day that was a metaphor of the political change: there was a single piper playing with a symphony orchestra. In other words, instead of promoting a martial Scottish-like piping formation, the new administration went back to the piper as a soloist, a mediator between the essence of the rural nation and classical music.

Yet the bagpipe has also been a key instrument in political protest. In 1995 the folk-rock band, Os Diplomáticos de Monte Alto [The Diplomats of Monte Alto], released their single ‘¡Eu quero ser gaiteiro!’ [I want to be a bagpiper!], which has become a war cry of sorts. In the words, several people including an Anarchist leader, Bakunin; the left-wing Portuguese musician, Zeca Afonso; a football coach, Arsenio Iglesias; and a mother are described as ‘gaiteiro/a’, meaning ‘hero’. A good example of this use of the instrument was the Marea Gaiteira [Pipers’ Tide], organised in 2002, as a political protest for the government’s mismanagement of the ecological disaster caused by the spillage of the oil tanker Prestige. More than 20,000 people attended this march and the bagpipe and the many pipers who attended were used as symbols of an empowered Galician community. Another example is the Piper Pussy Riot from the 2010 Women’s March where the image of a female bagpiper was used to protest in favour of women’s rights.

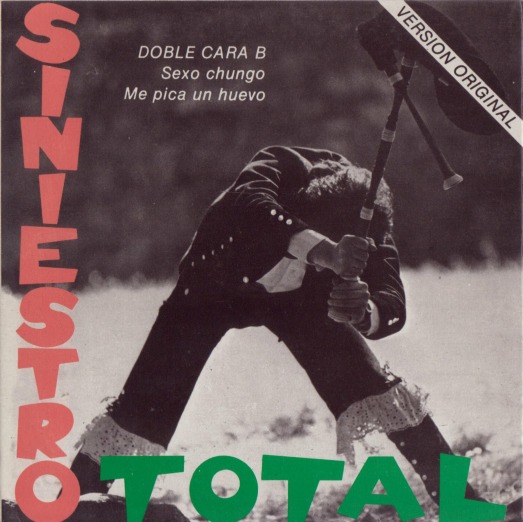

From folk music, the pipes have worked their way into other genres such as contemporary music, pop and rock. Two influential rock bands founded in the early 1980s, Os Resentidos [The Resentful Ones] and Siniestro Total [Beyond Repair], used bagpipes as symbols of their Galician identity. The former were the first rock band to have a bagpiper. The latter, the enfants terribles of Galician music, alluded to the cover of The Clash’s ‘London Calling’ when they chose, for the cover of their maxi single ‘Me pica un güevo’ [One of my balls itches], a bagpiper wearing the traditional dress smashing his pipes into the soil or digging the soil with his pipes. Once again, the instrument and the player are associated with a rural community but in the context of innovative musical genres.

The solo bagpiper regains the centre of the stage when Carlos Núñez releases his first album in 1996: ‘A Irmandade das Estrelas’ [Brotherhood of Stars]. ‘Nostalgia for the future’, as the writer Manuel Rivas wrote for this CD booklet. A few years later two female bagpipers launched their first albums: Cristina Pato and Susana Seivane. Here begins the great time of the solo bagpiper. All of them went from having more wholesome images on their first albums (highly skilled, wild or sensitive) to a more sophisticated and sexualised appearance on the following ones.

Since the 1980s, Galician media began making a wider use of the bagpipe and the bagpiper. So much so, that the Galician Regional TV station is negatively known as Telegaita. It is worth mentioning the successful Christmas campaign organised by a major regional supermarket chain, Gadis. Year after year, with a mixture of irony and praise, Gadis calls upon feelings of Galicianness, especially morriña, and uses bagpipes to convey an epic mode and bagpipers as superheroes: the supergaiteiro and supergaiteira [the Super Pipers], both of them with a sexualised image that echoes the image of the Scottish hero William Wallace in the Hollywood film Braveheart.

The tension between tradition and innovation is best seen in the type of instrument that bagpipers want to play. On the one hand, the tradition is closer than ever. The most significant historical recordings are now available thanks to the praiseworthy work of the label Ouvirmos. There are makers and pipers who work to bring back the sounds of the past, making and playing period gaitas. On the other hand, there are pipers who want to stretch the possibilities of the instrument. A well-known case is that of Xan Míguez González (1847-1912), the piper from Ventosela, who promoted the use of keys in the chanter. This line of research came under such severe criticism that it was soon abandoned. Since then, the changes to the chanter have been much more subtle. For example, some bagpipes have a new hole at the back of the chanter to achieve a semitone between the root and the second major. The makers are still working to improve the instrument, but they are careful to maintain its traditional look and shape. More recently, these efforts have been directed towards the piper’s playing technique—the extended technique is now applied to broaden the range of the repertoire.

The gaita and the bagpiper are everywhere we look. As images, we can find them in medieval stone carvings and manuscripts but also in modern souvenirs and supermarket commercials. From old wise men to young sexy (male and female) pipers, their image evokes ideas of longing and wisdom but also of heroism and playfulness. As literary motifs, they populate nineteenth-century writing but also pop and rock songs. From popular festas to official events, for centuries the gaita has been a fixture for all occasions. Regardless of they being traditional or innovative, the gaita and the bagpiper are uncontested symbols of Galician identity—their adaptability promises a bright future.

I would like to thank the Museo do Pobo Galego (Santiago de Compostela) and Clodio Gozález Pérez for their help with some of the images.

Cited sources

- Castro, Rosalía de. Galician Songs. Trans. Erin Moure. Sofia: Small Stations Press, 2013 [1863].

- Miguélez-Carballeira, Helena. Galicia, A Sentimental Nation: Gender, Culture and Politics. Cardiff: Wales University Press, 2015.

- Toro, Xelís de. ‘Bagpipes and Digital Music: the Re-Mixing of the Galician Identity’ (2002) http://bit.ly/Chanter20

- Pintos, Xoán Manuel. ‘A gaita gallega’ [1853], Trans. John Rutherford, from Breogán’s Lighthouse: An Anthology of Galician Literature. Ed. Antonio Raúl de Toro Santos. London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2010, pp. 122-123.

- Gemie, Sharif. A Concise History of Galicia. Cardiff: University of Wales, 2006.

- Campaign ‘Vivamos como galegos’ [Let’s Live Like Galicians] http://bit.ly/Chanter21

- Supergalegos [Supergalicians] http://bit.ly/Chanter22

- O escuadrón Malo será [The Brigade ‘It Will Be Fine’] http://bit.ly/Chanter23 http://bit.ly/Chanter24

- http://bit.ly/Chanter25

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!