This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

When I placed my order for a set of double chanter bag- pipes, I was given the first edition of this book as bed- time reading to keep me going whilst I waited for the pipes themselves. And I did read it cover to cover sev- eral times in anticipation. I’ve had my set of double pipes for just over a year now and looked forward to seeing the new version of the book.

This new and enlarged edition comes 11 years after the original book and 20 years on from Julian’s completion of his Cornish Pipes design. This second edition is bound, rather than the loose-leaf format of the original, and so is much more suited to regular use and carrying around in pipe cases.

The book reflects changes in the ways in which we access music since the first edition was published, so there are suggestions of websites of performers who play double pipes and video clips and tutorials on Julian’s website give support to the printed book.

There are 30 tunes which have been chosen as examples particularly suited to double chanter bagpipes. Most tunes are printed as the basic melody, then followed by a version split across two staves, one for each chanter. However, a few are only printed in the split stave version which I found a little harder to follow at first if the melody wasn’t already familiar to me.

I did enjoy the conversational style of the text, as if friendly advice from a tutor rather than formal instruction. I did come across very occasional typos, but there is nothing that loses the sense of what is being said and the book is clear and easy to under- stand throughout, which is great for pipers learning by themselves with only occasional chances to meet others.

A wonderful extra in this second edition is William Marshall’s handy approach to creating “chords” across the chanters, which I have personally found a great help in making more of these double-chanter bagpipes.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that this is solely a manual for players of Julian’s double chanter pipes, there is much to interest all bagpipers. There are several intriguing articles exploring themes relating to double chanter bagpipes, from carvings in medieval churches to the reconstruction of a double pipe described by James Talbot in the 1690s.

All in all, this is a very enjoyable book, being fascinating and useful in equal measure.

Available from: http://www.goodbagpipes.co.uk

George Stevens - 3 Tunes

Reviewed by Andy Letcher

An EP release from luthier and one time member of Snake-

town, George Stevens, consisting of two pieces for bouzouki

and one for bagpipe, all self-penned. As the names suggest,

‘2 Camels’ and ‘Age of Empires’ have an eastern feel, with

almost prog chord progressions at times (fear not, I mean that

as a compliment!), driven along by George’s steady percus-

sion. The sole bagpipe piece, ‘Polesworth Abbey’, is a

charming, medieval style waltz, composed while trying out a

set of Sean Jones pipes at the Blowout. George’s piping is

smooth and graceful with deft use of vibrato. He is accompa-

nied by the Kent Border Pipe Ensemble which, given the

otherwise assiduous sleeve notes, I take to mean himself performing a series of over- dubs. Here the mixing goes a bit awry, with the backing parts panned rather heavily and obscuring the melody, but this is nothing that can’t be fixed on what one hopes will be a full length album to follow.

Available from http://www.gstevensluthier.co.uk, £5.00 UK or £6.00 overseas.

Iain Dall (“Blind John”) MacKay was both a poet and a piper and one of the finest composers in early Highland piping history. He was born in 1656 at Talladale, Gairloch. He was blind from a young age and spent seven years studying with the MacCrimmon’s in Skye. He carried the composition of pibroch to a high level and eleven pibrochs can be attributed to him; for example ‘Lament for Patrick Og MacCrimmon’. As well as a piper, Ian Dall was a poet and bard of high status and a significant selection of his poetry has survived. He died in 1754 and in 1805 his chanter was taken to Nova Scotia by his emigrating grandson John Roy, where it was kept by generations of his descendants. No other chanter survives from any of the leading seventeenth- century piping dynasties.

The first time I was first told about the ‘Iain Dall’ chanter I was not especially interested in it. I certainly never anticipated that it would lead me into an odyssey which would affect many other areas of my life and my pipemaking. This ancient and frail chanter has somehow survived for over 300 years, having been passed down to the present day through an unbroken chain of people who have preserved it. It provides a unique link to a style of music that persisted in the Highland and Islands long after it had died out elsewhere.

My involvement with making Highland pipes goes back to 1990 when a German pibroch enthusiast, Andreas Hartman Virnich, commissioned me to make a copy of the ’earliest surviving set of pipes’. Hugh Cheape, who was then curator in charge of bagpipes at The Scottish National Museum, suggested the ‘Waterloo Drones’ and the ‘Mull’ chanter, both of which are now housed in The National Piping Centre Piping Museum,Glasgow. I measured these and copied them for Andreas and was impressed enough by them to make a copy for myself. They fascinated me, but as I do not have the background or ability to play Highland pipes and little experience of cane reeds, further developments got shelved.

In 1994 Dr Peter Cook, who was then Senior Lecturer in Music at The School of Scottish Studies, and had shown interest in these pipes, told me about the Iain Dall chanter and asked me if I was interested in going to Nova Scotia to measure it. I think it was Peter who gave me a blurred photocopy of a photograph of the chanter that had been published in the Oban Times in 1935. At that time I did not appreciate its importance and did not follow up his suggestion.

The turning point came when I met Barnaby Brown. In 1997 I had lent my own copy of the ‘Waterloo Drones’ and the ‘Mull’ chanter to Allan MacDonald. Alan had been researching and reappraising pibroch styles and his exciting and dramatically different performances were ruffling a few feathers in pibroch circles! He spent some time trying to reed them up and eventually passed them on to Barnaby. The moment Barnaby and I met we saw eye to eye. We both had an ‘Early Music’ approach to this project; he was just beginning to establish himself as a researcher and performer of the early pibroch repertoire and wanted to play on the best possible copy of an early Highland pipe. We both understood how important it was to respect original instruments and when copying them not compromise by altering measurements or hole positions in any way. His scholarly attitude rekindled my interest and his undaunted determination and zealous enthusiasm has remained the driving force behind this entire project.

Barnaby and I now cannot recall exactly when we set our sights on copying the Iain Dall chanter. A few other early chanters have survived in Scotland and Barnaby tracked down and inspected as many as he could. We wanted to copy one of them in as great a detail as possible to improve our skills in measuring and copying an historic chanter. We decided to focus our attention on the Black Chanter of Clan Chattan which is housed in the Clan MacPherson Museum, Newtonmore. It is an early chanter, with a delightful mythology that it was first seen being played by an angel in the sky at the Battle of North Inch of Perth in 1396! It is certainly an old chanter, quite possibly dating from the 17th century, but it has an ancient and substantial crack along the finger holes and does not show signs of having been played. We measured it in October 1999 and subsequently I made three copies, one of which Barnaby attempted to reed up using modern Highland reeds.

Having gained this experience we focused our attention on the Iain Dall chanter. The person who was the vital link in this project was the piper Rory Sinclair, from Toronto, Canada. Rory and I had become friends in 1996, when he was over on one of his annual visits to Scotland to the Piobaireachd Society Conference. At some time I had mentioned the Dall chanter to Rory in conversation and it turned out that he had known about its existence for several years. Better yet, he was a personal friend of the family who owned it. Furthermore, he had independently been thinking about how a copy might be made, so when he heard that we were also thinking about this, he enthusiastically offered to set the whole project up. He was the best person in the best position to arrange our trip to Halifax, Nova Scotia, which we made in December 2000.

It was then owned by Barbara Sinclair, the widow of John Mackay Sinclair, a direct descendant of Iain Dall. Barbara was elderly when we visited her and was delighted to find that we were showing such interest in the chanter which had been treasured by her late husband.

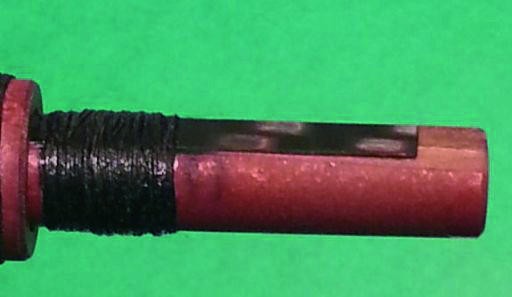

It was enormously exciting to see and handle the actual chanter during the two days we spent measuring it. We assumed that we would only ever get one chance so we had to be sure of getting all the information we required. It is a one-piece design with a graceful shape a bit reminiscent of some modern Spanish gaitas. It is professionally turned but now in poor condition as it is cracked and has broken in two around the bottom ‘devil’ (vent) holes. This has been repaired with a neat silver collar nailed onto the chanter with very short nails; a repair which may well have been made at least 200 years ago. The wood had shrunk to the extent that the chanter is now loose within the metal collar, which has also cracked. It is therefore impossible to play. The outside is bound with hemp between the finger holes. Much of this binding had become loose.

It clearly had been played for decades and it was fascinating to find that the finger holes show no signs of alteration or undercutting. Whoever had played it for all that time heard no reason to alter the intonation of the chanter whatsoever. We can be sure that the finger holes are exactly where the pipemaker originally intended them to be. Any tuning must have been done with wax in the finger holes or through the design and manipulation of the reed.

While inspecting it we also noticed a delightful feature; there is the double wear mark made on the chanter by the pinkie finger of the top hand, proving that it was played right hand high. This feature increased our reverence for it; it actually bears the direct marks of Iain Dall’s pinkie finger. It is clear that he held the bag under the right arm. At some point, someone has levelled the surface of the low G hole by hacking it down with a knife. They did this very crudely; you can see the knife marks. All the other holes are perfectly polished, which for a while we believed was worn down by piper’s fingers over decades of playing.

Barbara, and her sons Michael and Donald, could not have been more welcoming and helpful. We spent two days in Barbara’s house sketching, measuring, discussing and videoing the whole process. This involved inspecting it in the greatest detail, taking maximum and minimum measurements of the bore and outside profile. Wood does not shrink at the same rate across the grain as with the grain. The challenge with an instrument of that age is judging how much the wood has shrunk since it was in its playing prime. With regularly changing humidity in the bore the wood shrinks, more concentrically with the grain than radially. The result is an oval, or egg shaped bore, and by measuring both the minimum and maximum axes, one can try to estimate the circular diameter which the bore originally had. On returning to Scotland our first task was to take these measurements and extrapolate what we believe the original dimensions to be. We did this using a formula based on the research of recorder makers in the 1970s.

I made up a reamer and using my measuring probes on a test bore we compared the dimensions it produced to those we believed this chanter had in its prime. We repeated this fourteen times over a period of about four years, each time making fine adjustments to the reamer, filing it down here and there, until we were satisfied that it produced exactly the bore we wanted. Barnaby’s meticulous scientific approach was vital at this stage.

Compared to modern highland chanters, the existing throat on the Dall chanter is very wide. The throat is the short parallel section of the bore below the reed seat. When Barnaby took our first copy to reed makers they, without exception, expressed disbelief at the width of the throat. In the first years of usage the throat of a chanter often shrinks and benefits from being restored to its original diameter, but in the case of this chanter we found ourselves intentionally reducing the size of the throat to reduce the grief we were experiencing with reeds. However a couple of years later Barnaby persevered with the original throat size and discovered that it was simply a case of letting go of modern preconceptions of staple design.

We were delighted that in 2006 Rory got permission to bring the chanter over to Scotland for a week. He was delivering a paper on important piping artefacts in Canada to the The Piobaireachd Society Conference. Rory, Barnaby and I took the opportunity to give two other presentations about the chanter. One was at The School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh and the other at The National Piping Centre, Glasgow. Rory talked about the history of Iain Dall Mackay and his chanter. I talked about the challenge of copying it. Barnaby then played the chanter and talked about the challenge of developing a reed for it.

This visit also gave us a second chance to check some of our measurements and to compare my copies with the original. Mike Sinclair had agreed to allow a small sample of the wood to be taken for identification purposes. I managed to remove a minute sliver of wood from beneath the silver collar. This was identified by microscopic analysis at Kew Gardens as Guaiacum officinale or lignum vitae. This is the wood I am now using for my copies.

One of the benefits of this project for me has been that I have had to reassess some of the ways I work. Whenever I develop a new design of chanter I have the freedom to alter and adjust all the measurements. Once I have chosen the bore and wall thickness I can change the size and position of any of the finger holes to suit the chosen design of reed. But with the Dall chanter I do not have this luxury. My part in this project has been to measure and copy the chanter in as great detail as possible and I have studiously avoided the temptation to alter the evidence to make it behave in a way we imagine it should.

This has left Barnaby with the challenge of developing a reed that is perfectly suited to the chanter. Over the years he has pursued this task with bursts of fanatical zeal! This has involved him working with some of the finest Scottish reed makers and led him to designs which are substantially different from a modern Highland reed.

Highland bagpipe reeds have become so standardised that few modern reed makers have experience in altering these basic measurements. The tools used today make it harder to explore older reed designs; the requirements of mass production mean that older techniques, such as hand tying, are dying out. Barnaby has been privileged to work with some exceptional artisans who were willing to stretch out into the unknown, particularly Thomas Johnstone at Ezeedrone and, more recently, Andrew Frater. This process has had unexpected rewards, with the reed makers improving their standard product as a result of ‘research and development’ for the Iain Dall chanter.

What do the results sound like? Well, two myths have been exploded. The pitch of the Highland bagpipe in the eighteenth century was not as low as A440, but more like A455 , i.e. closer to a modern B flat. The instrument was also no quieter! The lower pitch does, however, give it a warmer tone, particularly compared to the chanters used in pipe bands today, which are sharper than B flat. Barnaby had cherished the thought of establishing what intonation the famous MacCrimmons preferred, as Iain Dall was one of their most outstanding pupils. He published results in 2009 which suggested ’that Highland pipers’ ideals of intonation and pitch have changed more since 1950 than in the previous 300 years’. Since then, however, progress in reed making and experience has reduced his confidence.

After Barbara Sinclair died, the chanter was inherited by her eldest son, Mike Sinclair. The interest shown in the chanter led him to the decision that the family should return it to Scotland after its 205 year stay in Nova Scotia. In November 2010, several members of the family flew over to officially donate it to the collection at the National Piping Centre in Glasgow.

Mike Sinclair had actually brought the chanter over in July and I was asked to undertake some conservation work on the loose binding on the outside of the chanter. It was rather daunting to be handed a cardboard tube with ‘Iain Dall Chanter’ written on the outside and being allowed to take it home for a few days. But it was a privilege to have one last chance to spend some time on my own with this priceless object.

It was also possibly the very last opportunity for Barnaby and me to recheck that our measurements actually tallied with the original chanter. And it was rather humbling to find that after all our efforts, when we placed the chanter on the drilling jig, we found that the positions of several fingerholes were slightly out. There is no substitute for working with the actual object one is copying and we would encourage anyone embarking on a project of this nature to transfer their measurements, not to pieces of paper, but directly to the tools of manufacture.

And it was also an opportunity to reflect on the journey that we have taken as a result of this chanter. As I am largely a self taught pipemaker, most of my skills and approaches have been learnt through a combination of trial, error and sharing and gleaning ideas with other instrument makers. Barnaby had no previous experience of chanter making and his healthy questioning of some of my assumptions and workshop practices proved very helpful. I admit that my initial reaction could sometimes be that of irritation! However it is sometimes beneficial for me to be shaken out of certain fixed ways that I have developed through working on my own. As a result I have made various changes in my approach to the way I make some of my other chanters. A vital realisation was to relate all measurements to a single zero point and to maintain this in the tools of manufacture. Otherwise, one cannot be confident about the interrelationship of the bore, the profile, the hole positions and the reed seat. With this chanter, our zero point was its base.

We have now been working on this project for eleven years and our collaboration has been a rewarding experience both on a professional and personal level. My practical skills and experience complement his analytical mind and have proved a powerful combination. We often have stimulating discussions about the chanter, trading and challenging theories, sometimes reluctant to abandon them. His insistence on making faithful reproductions of the chanter has even led me to compromise my principles of only ever using British hardwoods. I currently use lignum vitae for the Iain Dall chanter, but will also be making them in British hardwoods and I look forward to hearing the differences in tone.

When we started out on this journey we never anticipated that it would turn into such an odyssey. Looking back, we naively thought that after our trip to Nova Scotia it would only be a short time before we had a working chanter. Barnaby had bought some reed making tools and assumed that developing a reed would be a matter of a few months; job done! But we both lead busy and eventful lives and it has not always been easy to find time for our research and development work. The Breton piper, Patrick Molard, who has shown great interest in our project, eloquently described it as ‘a lifetime’s adventure’!

My own pipe making career has involved me recreating bagpipes from early images and from surviving 18th century pipes. In both cases, we know little about who played these pipes or their piping styles and techniques. The Iain Dall chanter is a complete contrast in that we know who played it, what music he played, and we even have the imprint of his fingers!

The importance of this chanter cannot be overstated; it has been described as the most precious relic of Highland piping heritage today. We know of no other chanter with a pedigree like it. The music that Iain Dall composed and played on it has its roots in a wider medieval tradition and it may be more accurate to view pibroch as a remnant of something British and Irish, rather than something specifically Scottish. This chanter is thus a ’time capsule’ which offers us a unique link to the past.

It has miraculously survived through an unbroken chain of people who have chosen to preserve it. I am proud to have become part of this chain by reproducing it. Making a copy may appear to be an end to me, but it is also a beginning for the piper who plays on it. They become the next links in this chain from the past to the future.

Barnaby is already giving concerts and recitals of Iain Dall’s compositions and there is considerable interest shown in it by other pipers who wish to explore the early repertoire of Highland piping on instruments of the period.

This has been a once-in-a-lifetime project. It seems symbolic that back in 2000 we were handling the chanter with our bare hands. As our respect and understanding for it has grown, we began handling it wearing cotton gloves. Now we have the satisfaction of knowing that Iain Dall’s original chanter is somewhere safe and visible, surrounded by pipers who appreciate its significance.

THANKS: We would not have been able to achieve any of this without the help, support and advice of many people. Especially Dr Peter Cooke, Rory Sinclair, Barbara, Mike and Donald Sinclair, Hugh Cheape and all of Iain Dall’s descendants who preserved his chanter.

The basis of this article was originally a paper that I delivered to The Piobaireachd Society Conference, Pitlochry, in March 2006. Since then it has been expanded and updated with significant input from Barnaby Brown.

For other discoveries on this odyssey, see “The Iain Dall Chanter: Material Evidence For Intonation and Pitch in Gaelic Scotland, 1650-1800” by Barnaby Brown in The Highland Bagpipe: Music, History, Tradition, ed. Joshua Dickson (Ashgate 2009).

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

You may need to scroll to find the article you’re looking for.

This edition is from our archives, so it is presented as scanned pages rather than text.

Swedish bagpipe reeds are traditionally made from the most suitable material growing in Sweden - Phragmites australis (common reed). Unfortunately Phragmites is a very fragile material and sensitive to humidity. Reed/tuning problems were most likely one of the main reasons that the instrument almost disappeared. Most active pipers today use imported cane, Arundo donax, the most common reed material for other reed instruments (including most other bagpipes). Arundo donax is harder and more resistant than Phragmites australis.

Even with Arundo donax reeds, however, many Swedish pipers struggle with their reeds on a daily basis. It is obviously a greater challenge to make single reeds work well for the full range of a chanter, than it is to make them work for the single note of a drone. This is a problem which the Swedish bagpipe has, or should have, in common with most East European bagpipes, but for some reason it seems to be worse for Swedish bagpipes. I can only speculate on why, but the narrow chanter bore, 6mm, might be one reason (possibly affecting stability). Another possible explanation is that many (most) Swedish bagpipe chanters were originally designed for Phragmites reeds. In any case, the full range of the chanter, a ninth or a tenth, is probably on the limit of what a single reed can handle, so the margins of error when making and adjusting reeds are very narrow.

Maybe for the same reason, it has turned out to be very difficult to make synthetic chanter reeds for Swedish bagpipes, i.e. reeds made from synthetic materials such as plastic or carbon fibre. A synthetic reed should be less sensitive to humidity and therefore more reliable in tuning and stability. Another advantage, which I think is almost as important for reliability, is that they should be easier to set up for consistent, perhaps even serial, production. With a reliable well-tuned reed, beginners could concentrate on learning how to play, instead of spending most of the time in frustration over misbehaving reeds, and it would make playing in groups a less painful experience.

However, it has been difficult to make synthetic reeds sound “right”, i.e. sufficiently close to natural reeds, and some would say that we are still not there. This is obviously subjective, and complicated by the fact that there is already a large sound variance among natural reeded Swedish bagpipes. In my opinion, the sound quality of synthetic reeds has now reached the point where they are within that variance. Not perfect, but close enough to make the practical advantages irresistible, to me and to a growing number of fellow pipers.

Synthetic reed tongues are not affected by moisture in the same way as cane, but this does not mean that they are trouble free. Though moisture cannot impregnate the tongue and thereby affect its stiffness, it can still affect its weight! If the humidity is high enough, the moisture may condensate and form small droplets on the tongue. If that happens, you will notice. On the other hand, you can then just wipe the tongue clean. (Cigarette paper is great for this - it’s thin enough to be inserted under the tongue to wipe that side as well..

Most of the usual tuning techniques for cane reeds should work also on synthetic reeds, but the tongue is often shorter than a corresponding cane reed which gives smaller margins of error when adjusting them. Also, even though cane reeds have their drawbacks, we’re used to them. Experienced pipers know what to do when things go bad. We don’t have that experience yet, with synthetic reeds, and the intended advantage that they don’t have to be messed with very often, gives us fewer opportunities to practice. So, when things do go wrong we may have lost our touch.

Below I describe the synthetic reeds made by three makers: Seth Hamon (USA), Matthias Branschke (Germany), and Max Persson (Sweden). These are not the only makers, but I would claim that they are currently the most influential in synthetic reed making for Swedish bagpipes.

I first came across the synthetic reeds (and bagpipes) made by Seth Hamon in the USA in 2011. I was giving workshops on Swedish bagpipes in Minneapolis and Seth Hamon, a bagpipe maker in Texas, kindly provided instruments on loan for the students. Both the ‘wooden’ parts of the instrument and the reed bodies are cast (!) in plastic resin and the reed tongues are cut from the kind plastic used in yogurt containers. The tongue is held in place by (movable) rubber rings.

Leaving the aesthetics (or lack thereof) of plastic instruments aside, they worked perfectly for their purpose. For the first time ever I could give bagpipe workshops without having to spend most of the time helping students with tuning issues. I spent less than an hour before the workshops tuning all the instruments, and that was it. After that they just worked. It was wonderful as a teacher, and surely also for the students, to be able to focus on playing techniques and styles during the workshop, instead of reed issues.

The sound, however, left some room for improvement. This is a matter of opinion of course, but there is to my ear a distinct sound difference between plastic reeds and cane reeds. They sounded ‘plastic’ (sic!) and they were a bit too strong (higher volume) compared to natural reeded Swedish bagpipes I played myself. But to a beginner I think it is more important to have a reliable instrument than that the sound is right.

I came home to Sweden with a bunch of plastic reeds and equipped one of my own instruments with them, to be used for practice and as a spare instrument, in case of emergencies during performances. This is the main advantage of Seth Hamon’s reeds, compared to the other two below. The reeds can be adjusted to work in most other Swedish bagpipes, not only the ones from Hamon’s own production. I adjusted mine for a set by Alban Faust. It took some time to get it right, Faust’s chanters are longer than Hamon’s, but it worked. The spare plastic reeds I got did indeed save two of my performances later that year.

The plastic tongue is soft and formable. You can bend the material to semi- permanent position, much like heat-setting cane reeds (but without applying the heat, obviously). So, there are many adjustments you can do, which is nice, but it is also a potential disadvantage. I do not expect two Hamon reeds to behave, or sound, exactly the same. The manufacturing of the reed body seems to be consistent, but the tongue and its tuning are not. The vibrating end of the tongue is very short compared to natural reeds, which means that small adjustments may have drastic effects. So, tuning them for the first time may be difficult, but once done it’s done.

Later that same year, at the Chateau d’Ars festival in France, I met piper and pipe maker Matthias Branschke from Germany. His reed bodies are made of phenolic paper (or something very similar) which is a fibre reinforced plastic, very hard and moisture resistant, commonly used for printed circuit boards.

The big difference compared to Hamon’s reeds is the tongue, which in Branschke’s case is made from carbon fibre and is absolutely straight. The elevation of the tongue over the body is not forced by lifting or bending. Instead, the bed under the vibrating part of the tongue has been grinded down to the correct angle, once and for all. Branschke has developed a rig specifically for this, and can do it with very high precision. (Hamon’s reed bodies are also grinded down in a similar way, but the tongue can be, and in my experience often has to be, bent a little anyway. This, and its softness, makes the end result less predictable..

Having an almost fully machined body and a straight tongue, Branschke’s reed production is very consistent, which is crucial because his reeds are not adjustable at all! There is no bridle or hair to move. Everything is fixed in place. Even if you tried to bend the tongue as you would a cane or plastic tongue, it would just snap back to its straight position again. The (somewhat risky) assumption made here, is that with a sufficiently consistent manufacturing process you should not have to tune anything but the pitch of the whole scale (to compensate for temperature changes). That pitch is adjusted by simply pushing the reed further into the chanter, or pulling it out.

I must admit that this inflexibility made me very skeptical at first, but the sound of the carbon fibre tongue was so much better than plastic, so I was intrigued. Sound quality wise these reeds are closer to cane, and I dare say that most people will not hear any difference at all (and, even if so, not more than the previously mentioned variance which should be expected from cane reeded Swedish bagpipes anyway).

In December 2011 I was invited to teach a workshop at in Germany. More than half of the students turned out to have bagpipes with synthetic reeds and most of them were Branschke’s. Again, I was able to spend most of the time teaching music and playing techniques, and very little time on tuning. Teaching is so much more fun and rewarding under such conditions, and I have come back to give courses three times since.

The drawback is that Branschke had to redesign the chanter and the chanter stock to make this work, and his reeds therefore only work in his instruments. Also, if (however unlikely) you do have tuning or stability issues, you can’t do much about it, at least not the way you’re used to with cane reeds. I’m used to being able to solve my own reed problems. Having said that, I do play a Branschke set myself now, and apart from some initial issues when coming back to Sweden, due to climate differences, I’ve had no problems with it since. (Knock on fibre reinforced plastic..

Max Persson is currently the only professional maker in Sweden who makes synthetic reeds. His reeds are a kind of mix of the other two – Branschke’s sound combined with Hamon’s adjustability.

Persson’s reeds have a plastic body and a carbon fibre tongue. As far as I can tell the material of the tongue is exactly the same as that of Branschke’s reeds. The tongue is longer, however, and the reed dimensions are in fact very close to those of cane reeds. Like Branschke, Persson elevates the tongue from the body by grinding down the body at an angle, but he does so under the fixed end, causing the tongue to jut out a bit (though the angle is very small).

Persson’s reeds are adjustable. Unlike Branschke’s reeds, there is bridle to move. In addition, the closed end of the reed body is plugged by a movable peg which can be inserted further into, or pulled out from, the body. This affects the scale somewhat, but also the sound.

The reeds share the good sound qualities with Branschke’s. There is very little difference, if any. The adjustability of Persson’s reeds should be an advantage, but on the other hand Branschke’s reeds do not seem to require adjustments. I have noticed that pipers with Max Persson reeds do seem to adjust them more often than I do (or would if I could) with my Branschke reeds. There is a risk that adjustable reeds adjust themselves, I guess, but in Persson’s case I don’t think this is the most likely explanation. I think the main reason is psychological: Pipers tend to mess with their reeds, not because they have to, but because they can, and are used to having to do so with cane reeds. Playing a Branschke set myself I don’t have that choice, so I don’t.

Unfortunately, the adjustability of Max Persson’s reeds does not imply that they will work in other instruments. Like Branschke, Persson has redesigned the chanter and stock as well, not just the reeds. Seth Hamon’s reeds remain the only ones (so far) which can be adjusted to instruments made by others, and are therefore also the only ones which are sold separately. Indeed, several other makers are now, on request, selling instruments equipped with Set Hamon’s reeds.

Sooner or later I think the synthetic reeds will replace cane for most of us. There will always be pipers, who prefer the old ways and materials of course, but to me the practical benefits of synthetic reeds are too great to ignore and the sound quality argument will not hold for much longer - not only because the quality will improve further, but because norms will move when most pipers play the new reeds. This has of course happened many times before, in Sweden and elsewhere.

More information on Swedish bagpipes, including links to all the makers mentioned in this article: http://olle.gallmo.se/sackpip.

@BagpipeSociety on X

(formally known as Twitter)

@BagpipeSociety on X

(formally known as Twitter)

TheBagpipeSociety on

Instagram

TheBagpipeSociety on

Instagram

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!