The Bagpipe Society

The Galician Gaita in Havana (Part II)

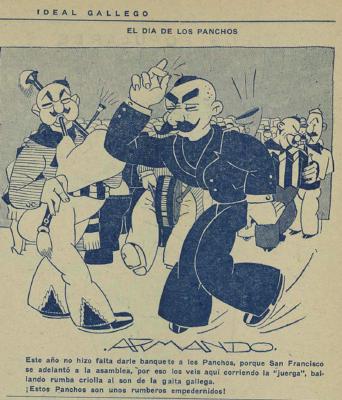

… por eso los veis aquí corriendo la “juerga”, bailando rumba criolla al son de la gaita* *gallega...

… that's why you see them here running the "party", dancing the Creole rumba to the* *sound of the Galician bagpipes...

El Ideal Gallego, Nº 84, 12th October 1929

In the same way that the history of Galicia cannot be understood without its emigration, Galician music cannot be explained without studying the bagpipe wherever the Galician emigration arrived. This article is the second part of “The Galician Gaita in Havana: a journey in time” published in Chanter in the winter edition 2022.

As a conclusion to the previous publication and as a starting point for this Part II, let’s remember that, from 1898, Cuba was no longer a Spanish colony and, despite this, many Spaniards did not abandon the island. In 1900 Galicians made up the 65% of the Spanish population that remained there. The musical and cultural scene in Havana echoed the Galician gaita and the figure of the Galician gaiteiro, both becoming icons in the representation of Galicia. In 1904, in Havana Recordos d’un vello gaiteiro (Memories of an old bagpiper) was performed, a play written and directed by Nan de Allariz and presented for the Centro Gallego audience. As Iglesias Cruz states, the events organised by the Galician Centre in Havana demonstrated a " show of power and mobilisation capacity". At that time, the Galician Centre ( Centro Gallego) had more than 20,000 members. It is therefore possible to deduce the impact that these specific representations had on Havana society.

Also, Pinheiro Almuinha points out, another remarkable example in the theatre of manners (teatro costumbrista) and in the zarzuela performances too, where it was common to include on stage a gaiteiro (bagpiper) and a tamborileiro (drummer). The zarzuela Maruxa by Amadeo Vives stands out from the rest for its quality and number of performances. The greater the popularity of the play, the more important was the selection of the solo bagpiper. Likewise, apart from the Centro Gallego Theater, the most relevant plays became part of the billboard of the main theatres in the city, such as the Teatro Payret.

While the gaita and the gaiteiro had a starring role and a well-defined aesthetic, the 20th century marked the continuity as well as the beginning of a new era, what is to come in this article: “Dancing Creole rumba to the Galician gaita tunes”. It is difficult, if not impossible, for political change to get rid of cultural habits rooted in time.

A rumba I will play…

In the Cuban musical scene at the beginning of the 20th century, both Galician and Spanish tunes and rhythms were interspersed with national ones, among which it is important to highlight those with African origins, such as guarancheros, popular troubadours, black curros and guaguancó choirs. The guaguancó is a popular expression in which one or more soloists improvise a theme or motif over the rhythm of a rumba. The rumba genre presented several styles, one of which was called "rumba de tiempo España" (Spanish beat rumba), characterized by a slow rhythm. Examples of these cultural exchanges and even hybridizations are preserved in the Galician popular musical heritage. The following Galician refrain shows the naturalness with which Galician musicians integrated themselves into peasant populations in Cuba:

Mándanme toca-la rumba ( They ask me to play the rumba,) y eu a rumba non a sei; (but I do not know the way;)

Para quen entre no baile (But, for those who want to dance)* *unha rumba tocarei. (a rumba I will play.)

Peasants improvised on daily events bringing to light their rhythms and practices whilst also acquiring foreign ones too. The gaita was the only instrument, the most popular was the bandurria and the tiple as well as the use of stools, glasses and bottles to beat the rhythms. But, the Galician settler who arrived with his own bagpipes was welcome to participate and this interaction became more and more familiar.

The Galician population which remained in Cuba from the late 19th century and throughout the 20th century was characterised by its rapid adaptation and integration into the island's culture without losing its own identity, although sometimes it goes unnoticed. As Fernando Ortiz stated:

“Havana was the centre where all the music melted with the greatest warmth and the most polychromatic iridescence.” Despite it is not always being easy to follow the trail of Galicianness in Cuban music, if not through the gaita, it is important to note that behind the racial mixing and the mulatto appearance in some of the most prominent figures in Cuban popular music, there are Galician and Asturian roots. For example, Miguel Faílde (Matanzas, Cuba; 1852-1921) whose father was from Galicia and his mother was from Matanzas. Faílde was the first great promoter of the danzón. Nowadays, to say that he was the “creator” of this popular rhythm and dance is very risky, but his composition entitled “Las alturas de Simpson” (Simpson's Heights), released in 1879, marked definitely a before and after in the evolution of the danzón. A few decades later, another example is Ignacio Piñeiro (Havana, 1888-1969), a Cuban musician, founder of the Septeto Nacional orchestra and considered one of the most important exponents of Cuban son and its variants. Piñeiro was a mulatto whose father was from Asturias, a region located in the north of Spain, next to Galicia. From an early age, Piñeiro participated in children's choirs in the city of Havana and later formed part of different popular groups such as Los Roncos and Timbre de Oro. It was in the year 1926 when he composed "Asturias, patria querida" (Asturias, dear homeland) in honor of his father who returned to his birthplace before dying.

Miguel Faílde and Ignacio Piñeiro’s DNA, like that of many others less popular and still unknown musicians, represents a parallel of what was happening with music in Cuba. If the Galician presence was not evident at first sight, its reminiscences show in various ways.

Sunday and its festivities, a new musical scene.

Most of the Galicians who emigrated to Cuba were peasants and their main aim was to find a job. It is for this reason that, at first, they did not get involved in the social, cultural and political activities of the Galician Centre in

Havana where it was more usual to find the bourgeoisie. But, as the 20th century progressed, more migrants avoided the countryside preferring to settle in the city where they could find different job opportunities such as waiters in the popular

“bodeguitas”, restaurants and hotels, but also as doormen, cooks, bakers, peddlers. There were many opportunities for those who had learned a trade in Galicia because in the cities there was great demand for various trades such as umbrella makers, wheelwrights, cobblers, construction workers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and even watchmakers. Before long, there was a more established Galician community in the city. Between 1900 and 1935 the number of Galician inhabitants in Cuba escalated from 19,088 to 40,100.

The working day for a Galician was around sixteen hours, and they only had Sunday afternoons off every fortnight. This is when Sundays began to be understood as the “resting day”. Music bands came out to the streets, the promenades were expanded and one of the most influential occurrences of the first half of the 20th century in Havana was the construction of the “Jardines de La Tropical” (La Tropical Gardens) - an exclusive recreational area whose gardens were the thermometer of popular dance music in Cuba. These open-air salons spontaneously attracted people and there was no requirement to wear tails or fancy dresses. Immigrants of Hispanic heritage, found La Tropical to be the best place in town to celebrate their Sunday gatherings where foreign music was offered, such as pasodobles, charleston, onestep, fox-trot, without forgetting waltzes, polkas, mazurkas and the popular danzones.

A minority of the Galician migrants who regularly attended these events, also had the ability to play the gaita because they had learnt it in their childhood or adolescence in Galicia. In Havana they were in great demand to liven up parties organised exclusively by the different Galician societies. But, only a few former members of the military bands were able to dedicate themselves to music as their primary activity, for the rest it was relegated to a second activity or to leisure time.

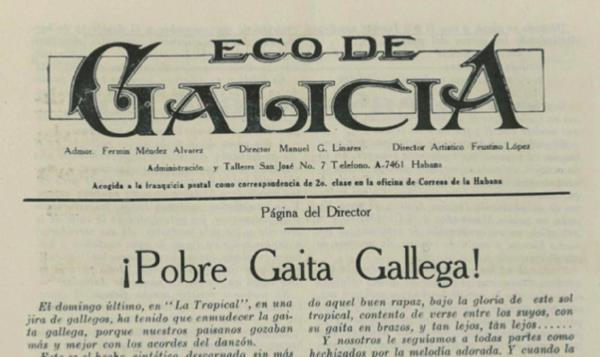

During this period, the new danceable rhythms and the instruments to perform them burst onto the Cuban scene with such force that, for a while, they overshadowed the traditional ones and the gaita was relegated to the background or even disowned. As mentioned at the beginning, the gaita seemed to be stuck with traditional representations and functions. This fact was vindicated in the Galician press in Cuba, stirring the conscience of the community. One could read alarming headlines such as "Poor Galician gaita!" or “When the gaita falls silent”.

The following article, from 1918, describes how the gaita was ignored by the Galicians attending a Sunday gathering at La Tropical gardens.

What happened on Sunday in "La Tropical" has no name; it was a real defeat for the regional gaita. A young man from Ourense, who by the cut of his clothes showed that he had just arrived in these lands, was the bagpiper. He was a very well-known and appreciated young man among his compatriots; cheerful, jocund, "boisterous"; with that joy and good humour characteristic of Galician youth, and which is the most resounding lie to the reputation of being gloomy and hermetic hat fantasy novelists have given us. (…) The gaita wanted to be played again, but the stridencies of the metal and the booming of the timbalero, marking the first bars of a danzón, silenced it definitively. (…) The Galicians waited impatiently for the other danzón. The echoes of the gaita, which sang nearby, said nothing, sounded like nothing, did not reach the hearts of those sons of Galicia. Poor alician bagpipes! The bagpiper made a gesture and let his gaita deflate, the last sound of which sounded like a sob…

Eco de Galicia :Ano 2 Número 50 - 1918 xuño 16

Fortunately, this situation was not to last long. As stated by Óscar Ibáñez, although the Galicians brought their traditional rhythms to Cuba, such as the muiñeira, alalá and alborada, they were also familiar with the new genres coming from Europe.

This helped them interact with the local and American genres and rhythms in vogue at that time. In addition to the rumba,

the danzón, in its full glory, grabbed the attention of the Galicians who dedicated a special place for it in their repertoires. The gaiteiros were exposed to musical exchanges with other immigrant musicians on the island or former Spanish soldiers. Because of this quick adaptation, Galicians rapidly increased their repertoir and this enabled them them to not just be observers but participants, and sometimes leaders, of the new musical ensembles.

In addition to the playing expertise of these gaiteiros, it should be added a no less important skill, which was knowing how to repair the gaitas or even how to make new ones and, of course, the making of the indispensable reeds.

It is from this point onwards that the gaita and the figure of the gaiteiro rather than decline, had the ability to adapt and integrate into the new musical scene. After the sporadic musical ensembles who were “sneaking” into the parties, formed by gaita, snare drum and bass drum, a more attractive format was established in the early 1920s: the quintets with gaita. These musical ensembles consisted of: gaita, clarinet, cornet, snare and bass drum. As Ibáñez states:

The Galician bagpipe become part of ensembles in charge of performing in parades such as the "Quinteto Regional de José Cortés" in Matanzas or the "Quinteto de José Páez" in Havana, in which Gelacio Martínez played the gaita.* In 1929 the "Quinteto Barcalés" led by José Tomé Castro, who was later replaced by Gelacio Martínez, was established in Havana. Between 1929 and 1939, the quintets composed mainly of gaita, clarinet, saxophone, snare drum and bass drum with cymbals underwent a process of standardisation, conquering a space among the orchestras and dance music ensembles within the framework of the celebrations of Spanish societies. Their repertoire included all kinds of danceable rhythms of Galician, Hispanic, Cuban and North American origin, as well as soundtracks from the fashionable films of the time. The most important were the "Quinteto Barcalés" and the "Quinteto Monterrey".

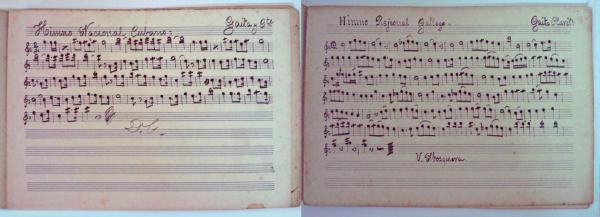

In the splendour decades of La Tropical gardens, the gaita continued to be heard. The gaiteiros, themselves, created new compositions updated and dedicated to the social context of the time. Among the repertoire of the “Quinteto Monterrey”, one of the most popular quintets mentioned above, there are titles for every special occasion, a medley of genres whose headings mention singular occasions either of their life in Havana as well as recalling Galician memoires, words or traditions. Some of them are “Dominguito” (little Sunday), which is an habanera; a pasodoble entitled “Los larpeiros del Vedado” (Vedado is a neighborhood in Havana and “larpeiro” is a Galician word that means “glutton”, a person who eats a lot); the muiñeira “Empanada de pollos” (Chicken empanada); a jota entitled “La fuente del Sapo” (The fountain of the Toad) to evoke a spring located in Verín, Galicia. Curiously, one thing that could not be missed in the repertoire were the national anthems. José Posadas, for his Quinteto Monterrey, transcribed the Cuban National Anthem and the Galician Regional Anthem. Regarding the latter, it is important to contextualize that the Galician it was not recognized as an official anthem until 1978. The role played by the Galicians in Cuba was key to its achievement.

The standardization of these particular quintetsand their participation in different events and celebrations of the heterogeneous Cuban society beyond the gardens, undoubtedly gave the gaita a boost. So much so that in October 1929, a parodied image of the bagpipe appeared in a cartoon on the occasion of the Columbus Day celebration.

The use of the gaita was maintained until at least the 1940s, when the musical and social panorama was immersed in new trends and the musical ensembles had to adapt to the new requirements: new party rooms, new acoustics and a new wave of rhythms and instruments replaced the role of the gaita.

This article aims to highlight some of the singularities of the Galician gaita in Cuba during the first decades of the 20th century. Thank Óscar Ibáñez for sharing the photographic material belonging to the personal archive of José Posadas (Verín, 1885 - Havana, 1955), a Galician emigrant to Cuba and leader of the Monterrey Quintet.

Related readings / Works of interest:

Guanche, Jesús. España en la savia de Cuba. Los componentes hispánicos en el etnos cubano. La Habana, Ediciones CIDMUC, 2013.

Ibáñez García, Óscar. O “Quinteto Monterrey” de José Posada: nos xardíns da Tropical. Pontevedra, Dos Acordes, 2009.

Iglesias Cruz, Janet. “Galicia y los gallegos en la política de Cuba”. Novas achegas ao estudo da cultura galega II. Olivia Rodríguez (ed.), Universidade da Coruña, 2012.

Linares, María Teresa. La música y el pueblo. Instituto Cubano del Libro, Editorial Pueblo y Educación, La Habana, 1974.

Pinheiro Almuinha, R. A La Habana quiero ir: los gallegos en la música de Cuba. Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco, 2008.

Santamaría Cadaval, E. “The Galician presence within the Wind Bands of Havana in the period between 19th and 20th centuries”. Bandas de música: contextos interpretativos y repertorios. Nicolás Rincón y David Ferreiro (ed.), Libargo, España, 2019.

estibaliz@unhanoite.gal

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!