The Bagpipe Society

The Galician Gaita in Havana

Galicia, ese territorio máis imaxinado que percorrido, tras dos ecos dunha gaita…

Galicia, that territory more imagined than travelled while chasing the echoes of a bagpipe…

Xabier L. Marqués

When in 1996 The Chieftains recorded the album Santiago, they highlighted the value of the music of the north-western Iberian Peninsula and its connection with America. At this time, Paddy Moloney argued that "Galicia is the world’s most undiscovered Celtic country". Although Galicia belongs to the universe of the Celtic World, it was around the 1970’s onwards that Galician traditional music and folklore started its process of revitalization with bands like Fuxan os Ventos (Lugo, 1972) and Milladoiro (Santiago de Compostela, 1978).

These bands made a name for themselves on the Celtic musical scene and also foreign bands contributed to the internationalization of Galician tunes, such as The Chieftains releasing the album mentioned above and even by boosting the career of the Galician gaiteiro Carlos Núñez. Another outstanding example is Mike Oldfield's collaboration with Luar na lubre (A Coruña, 1986). In 1996, the British musician included an adaptation of their song O Son do Ar renamed as The Song of the Sun, on his album Voyager and invited the Galician band to his world tour, making Luar Na Lubre world-renown.

Now, back to the above-mentioned album Santiago, The Chieftains emphasized that “Cuba has a very close relationship with Galicia” and for the recording they featured the collaboration of Cuban musicians, most of whom belonged to the Buena Vista Social Club project. But, how far back does this Galician-Cuban relationship go? Undoubtedly, the most dynamic period was the late 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, due to the largest migratory process in the history of Galicia.

Therefore, in the study of the Galician bagpipes ’ gaita galega’ and its presence in Havana, it is essential to bear this emigration period in mind.

This article wants to highlight the role the gaita played in Cuba during the 19th century and especially to focus on how the Galician elite used it as a symbol of sensitization in the shaping of Galician identity.

Brief context

By the second half of the 19th century, Galicia was going through one of its greatest economic and social crises, from which it was unable to recover. The perennially lagging industrialization, the deterioration of the peasant industry, the severe agrarian crises, plagues and diseases, led to a long phase of degradation and impoverishment among the population. This social and economic situation deteriorated significantly contributing to a massive Galician emigration. In this process, two social realities were present in both the rural and urban sectors: on the one hand the large impoverished lower class and on the other the bourgeois, a minority, together with the intelligentsia.

The main point of destination at that time was the island of Cuba for several reasons, such as it was a Spanish colony and one of the main sources of wealth that supplied Spain with products like sugar. The great demand for free labour due to the boom in sugar cane cultivation was intensified towards 1880, the year in which slavery was abolished (Almuinha, 2008).¹

Havana, which had been a walled city since the 17th century, began to transform itself from 1830 onwards, expanding its urban area. The Prado promenade was extended to the seafront and new parks and gardens were created, as well as spaces dedicated to leisure activities such as musical societies and theatres. Music acquired a greater presence in these spaces open to the general public and the brass bands, although at that time most of them were military bands that obeyed the patterns set by the Spanish army, became a key element in the dissemination of a wider musical repertoire.

Despite its Spanish colonial status, little by little the Cubans sought their autonomy and, as in any colonizer/colonized situation, the role played by Cuba lead first to a socio-economic intern crisis and, right after, political armed conflicts

broke out increasingly intense. Throughout the 19th century, the Spanish government sent a continuous military reinforcement to strengthen the army in its struggle to maintain political authority in the colony. These Spanish-Cuban tension generated great instability on the peninsula, and the lack of resources was compounded by the administrative instability of a country that was already immersed in its own fin-de-siècle crisis.

Since the Ten Years' War (also known as The Big War) between 1868-1878, the military presence requested by the Spanish colony on the island of Cuba increased and, in the last years of the colonial period, during the War of Independence between 1895 and 1898, took place the greatest military reinforcements: Spain sent to Cuba 220,285 soldiers² (Moreno Fraginals, 2003), adding to this figure more than 50,000 volunteers (Moreno Fraginals, 2003). The inequality between the territories of Spain was notable and, faced with the urgency of recruiting men to fight in the war in Cuba, the army turned to the poorest regions, those where the people were most in need and Galicia was one of them.

It is well known that the lower echelons of armies are drawn from the lower classes. For a long period Galicia suffered hardship and, a situation similar to the Great Famine – the extreme period of hunger undergone in Ireland between 1845-49 – also occurred in Galicia in 1853 and it was called ‘O ano da fame’ (The Year of Famine). All these misfortunes motivated Galician population, mainly young people, to emigrate, if not by paying for their own boat fare, by joining ‘for free’ in the army in case of the men, and, in the case of women, serving as nurses in the field hospitals.

Could this uncertainty and precariousness long-lasting situation be the origin of the melancholic expression that distinguishes the Galician accent, so well-tuned by the bagpipe and also evoked in the popular songs of this territory?

In the 19th century, the gaita in Galicia regained its presence in social and liturgical events. It was also an instrument that had a notable incursion in the military bands but, despite being the instrument "par excellence", it was not an accessible instrument in all families but rather it was a piece generally passed down from father to son. Thus, among the large emigrant population, few emigrants were lucky enough to be able to take the bagpipes with them on the ship overseas and, moreover, to earn an extra salary playing them.

Galician political influence in Havana in the 19th century: the Gaita used as a strategic tool

From 1840 onwards, Havana became one of the most important nerve centres of the Galician intelligentsia and bourgeoisie. Although they were a 20

minority, they were very active and prolific, creating associations and very fruitful journals whereby they framed an increasingly strong ideational-identitarian discourse. These organizations supported social and charitable work as well as promoted cultural, recreational and political activities. All to demonstrate or purporting to demonstrate that the regional dominance of emigration was palpable.

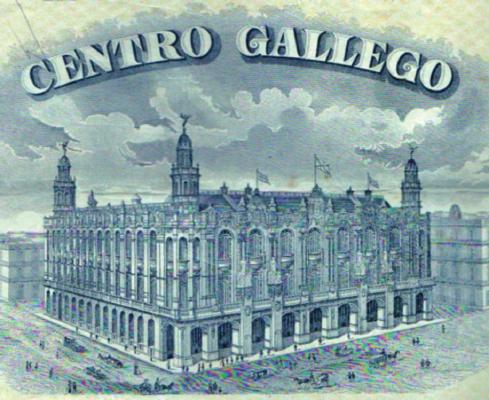

In 1871, the Sociedad de Beneficencia de Naturales de Galicia (Galician Charitable Society) was founded in Havana to: "provide its members with health and social assistance; instruction, recreation and shelter for those who were useless for work. To pay attention to the Galician immigrant; to contribute to the enhancement and prosperity of the native country, spreading its language, its glories and beauties; to promote the union of the children of Galicia and their descendants" 21; and in 1879, under its aegis, the Galician elites founded what was to become its greatest asset, the: Centro Gallego de La Habana (Galician Centre of Havana).

In Cuba, as well as in Galicia, militarism was part of society and was linked to political and cultural life. Although the main objective of the military reinforcement was to prevent the loss of the colony, another no less important one was to keep society at ease, distracted from what was happening on the battlefields. It was customary for military bands to play weekly in barracks

and fortresses, but little by little they began to expand their musical activity by playing in the main squares and avenues for non-military audiences. As the military bands acquired a greater presence in the city, they became key to the dissemination of a wider musical repertoire, including the musical tastes of the time among which there was no lack of Galician tunes. It is important to recall that between 1885 and 1895, 34.24% of Hispanic immigration in Cuba was from Galicia.

After the outbreak of the Cuban War of Independence, in 1895 the Centro Gallego vigorously supported the Spanish army and organized reception parties for the troops arriving from the Peninsula and shows to raise funds for the treatment of the wounded and for the creation of a stronger Navy.

In Cuba, as well as in Spain, the colonial army encouraged the formation of military music bands and promoted their activity more widely. The first references to Spanish soldiers playing in military bands in Havana date from 1830³. The Galician presence in the military bands was not only appreciated by the number of Galician soldiers, but also by the incorporation of the gaita galega in some regiments and battalions. The Galician soldiers and high-ranking military commanders who embarked from Spain for the war in Cuba accompanied their songs with the gaitas and this instrument aroused a strong patriotic feeling among the Galician people.

The gaita played a symbolic role in the historical construction of Galicia as a nation. The gaita ʺpossesses an estimable political charismaʺ⁴ and those in power knew how to use this instrument with the concrete political intentionality of raising awareness among the Galician population on the island, to stimulate the commitment of its soldiers and to demonstrate support for the Spanish army forces. The presence of the gaita in the colonial army and the significant boost received from the elites contributed to the circulation of Galician music in the wind bands repertoire and the use of the bagpipes in these scenarios. This led to a musical exchange combining their homeland musical tunes and patrons with other Spanish and Cuban ones. Galician rhythms were increasingly in demand and muiñeiras and jotas became part of the repertoire of the military bands in Cuba.

Before continuing, I must make a point to explain that the muiñeira is a genuine popular dance from Galicia and, therefore, also the rhythm and music with which it is danced. The name given to this musical genre comes from ’ muiño’ that means stone “mill”. It was there, where the grinding of corn and wheat was carried out, where this dance originated. Around this work space the farmers danced, sang and played muiñeiras with the gaitas and this everyday life become a point of reference for the migrants and a literary device for the contemporary poets, writers and musicians who reflected this in their works.

We must not forget that, at that time, in the late 19th century, Galician culture was immersed in the Rexurdimento, a powerful nationalist movement influenced by the romantic ideal that implicitly carried a sense of national affirmation, as a result of ideas derived from the European Romanticism.

Getting back to the main topic, in the face of the desperation of the Spanish army in the struggle to maintain possession of the island of Cuba, the gaita played a role of sensitization. In 1898, the commander of the cruiser-battleship Vizcaya, Antonio Eulate Fery, played an ' alborada’ with the gaita on his arrival at the port; and there is evidence that the bagpipes were present in those regiments where there was a greater presence of Galician soldiers. Two years before, in 1896, the board of the Centro Gallego in Havana gave a gaita galega as a gift to the first company of the Zamora Battalion in support of the Spanish army during the War of Independence. For this occasion, the Galician writer Lugrís Freire (1863-1940) composed in Havana some verses which he recited at the presentation ceremony, encouraging the Galician soldiers. The poem, which Pinheiro Almuinha includes in his book, reads as follows:

| ¡Toca, gaiteiro, con ira | Play, bagpiper, with anger |

| unha cántiga de guerra, | a war chant, |

| facendo que como un trono | making the reed resound like a thunderclap! |

| repenique esa palleta! | |

| ¡Toca a muiñeira da morte, | Play the muiñeira of death! |

| !toca a sinistra muiñeira! | play the sinister muiñeira! |

| ¡Toca, gaiteiro, con modo | Play, bagpiper, play with success |

| unha sublime muiñeira, | a sublime muiñeira, |

| a que lle tocan ô cális, | the one played for the chalice, |

| ô xuntalo c’a patena! | when joining it to the paten! |

| ¡Toca a muiñeira da groria! | Play the muiñeira of glory! |

| ¡¡Toca a muiñeira gallega!! | Play the Galician muiñeira!!!" |

(author’s translation)

The author of this poem plays with two inherent symbols of the Galician collectivity: the gaita and the muiñeira. They both were already being defined as the flagship of Galicianness, along with the figure of the gaiteiro (the bagpiper) in the Galician political discourse. The differential desire has played a decisive role in the construction of a musical past. The gaita and the popular genres of Galicia ( alalá, alborada, muiñeira) were praised by the elites and the major musicians of the military bands composed works for band with Galician airs.

In the Galician literature of the 19th century, some Galician writers drew their inspiration from the Gaelic and Scottish Highland legends. They adapted fictional war scenes to Galician battle zones and so did with the bagpipes becoming almost a sacred symbol. Anecdotally, in the press they used portraits of Scottish bagpipers, as if they had fought in Galician battles against the French in 1809, whose misunderstandings created light-hearted and sympathetic debates.

Thereon, in a process of recognising their own culture and heritage, Galician literary renaissance poets such as Rosalía de Castro y Manuel Curros Enríquez dedicated poems to the figure of local salient pipers, such as Un repoludo gaiteiro (A chubby piper) or O gaiteiro de Penalta (The piper from Penalta).

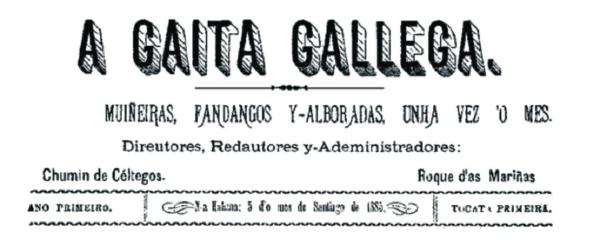

Beyond its proper musical use, the gaita acquired a different meaning far from the parameters of an eminently musical object. Thus, it was in Havana and not in Galicia that the first periodical publication written entirely in Galician language and not in Spanish, was published between 1885 and 1889. In it, they reported events and everything that happened on the island and were linked in some way to the Galician community, as well as the news that arrived from overseas. Interestingly, this periodical publication was entitled, A gaita gallega (The Galician Bagpipe). This demonstrates how the gaita galega was acquiring a symbolic significance.

Despite the impending political changes in Cuba, when in 1898 the Spanish rule was overthrown many Galicians refused to leave the island and return to Spain, at the same time that the immigration remained active in the relentless pursuit of a better future. The Galicians who remained on the Island served as a bridgehead between Cuba and their places of origin in Galicia, and exercised a convening power among his compatriots. It should be remembered that Fidel Castro's family was of humble origins from a small peasant village in Galicia, and his father landed in Havana in 1899, just when the United States officially took over the Island's government.

During the decade that ended and opened the way to the new century, musical activity did not diminished, but shifted from the military to the civilian sphere. The bands of the colonial army were disbanded and musicians were reorganized becoming part of the new municipal or national bands or those linked to an association, as was the case of the Banda España. In 1900, Galicians made up 65% of the Spanish population in Cuba. The continuous growth of the Galician population on the island justifies the fact that both Galician customs and music remained active. As a curious fact, in 1907 the Municipal Band of Havana officially presented what from 1978 onwards would become the National Anthem of Galicia.

The gaita and the figure of the gaiteiro did not fade away but continued to be active in the musical scene and also played a remarkable role in the costumbrist theatre and zarzuela performances, such as Memories of an old bagpiper, a monologue wrote and directed by Nan de Allariz and presented for the Centro Gallego audience in 1904. This work marks the end of an era and the beginning of what is to come: “Dancing rumba criolla to the Galician gaita sound”.

TBC!

Related readings / Works of interest:

- Campos Calvo-Sotelo, J. Fiesta, identidad y contracultura. Contribuciones al estudio histórico de la gaita en Galicia.

- Guanche, J. España en la savia de Cuba. Los componentes hispánicos en el etnos cubuano. La Habana, Ediciones CIDMUC, 2013.

- Iglesias Cruz, Janet. “Galicia y los gallegos en la política de Cub”. Novas achegas ao estudo da cultura galega II. Olivia Rodríguez (ed.), Universidade da Coruña, 2012.

- Márquez Sterling, C. Historia de Cuba desde Colón hasta Castro. Nueva York, Las Américas Publishing Company, 1963.

- Moreno Fraginals, M. R. y Moreno Masó, J. J. Guerra, migración y muerte. El Ejército Español en Cuba como vía migratoria. Gijón, Ediciones Júcar, 2003.

- Pinheiro Almuinha, R. A La Habana quiero ir: los gallegos en la música de Cuba. Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco, 2008.

- Santamaría Cadaval, E. “The Galician presence within the Wind Bands of Havana in the period between 19th and 20th centuries”. Bandas de música: contextos interpretativos y repertories. Nicolás Rincón y David Ferreiro (ed.), Libargo, Spain, 2019.

References

- Pinheiro Almuinha, R. A La Habana quiero ir: los gallegos en la música de Cuba. Santiago de Compostela: Sotelo Blanco, 2008, p. 33.

- Moreno Fraginals, M. R. y Moreno Masó, J. J. Guerra, migración y muerte. El Ejército Español en Cuba como vía migratoria. Gijón, Ediciones Júcar, 2003.

- Pinheiro Almuinha, Ramom. A la Habana quiero ir. Los gallegos en la música de Cuba. Santiago de Compostela, Sotelo Blanco Ediciones, 2008, p. 80.

- Campos Calvo‑Sotelo, J. Fiesta, identidad y contracultura…, p. 151.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!