The Bagpipe Society

What is a Smallpipe?

Dear Jane,

I wonder if I might tempt you to write a general article on the categories of kinds of smallpipes and their differences. The reason I ask this is because I am learning the chanter/pipes and, because I live in a townhouse, buying a set of Great Highland pipes is not an option for me at this stage. I do want to be able to move on to them someday so I personally want standard hole spacing on a smallpipes chanter and in key of A etc. It has taken me a good 6-8 months to actually figure out what my options are, as the variety of small pipes is so bewildering. It was only near the end of my research that I realised that the majority of small pipes are tuned an octave lower than the Great Highland pipes. The reel pipes seem to be the only pipes that have the higher tuning, although it is almost impossible to get some without a common stock (FYI, I finally found that lovely Fred Morrison would make reel pipes with individual drones). So, I only mention the idea of a possible general smallpipes article as I had such trouble sorting out the smallpipes quagmire.

Penny Whitehouse-Vaux

The above correspondence was forwarded to me by the Chanter editor and, as she is not an expert in the field of smallpipes, she asked if I could help out by writing about the instrument.

At first glance I assumed that people would know what Smallpipes were but when I cast my mind back to my early days of bellows pipes, I had a journey of discovery to make.

My background of learning the Highland pipes from the age of seven gave me a perception of a bagpipe and I assume that this would be different to someone who hasn’t any piping tradition on their doorstep. When I set out on my journey, information regarding smallpipes was very limited, whereas now there is a wealth of information but too much can be confusing. First of all, we should define what a Smallpipe is or isn’t. Small pipes or Smallpipes? We seem to have settled on all one word as the noun and the small being the adjective.

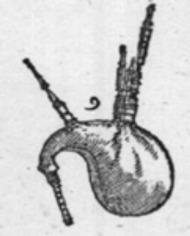

Is it their size that makes them small? The Biniou kozh is a Smallpipe but they are not necessarily what we mean by smallpipes as the Biniou has a conical bore, which will put it up an octave and it is also extremely loud. So, one of the defining features seems to be that it has a parallel, cylindrical “clarinet” bore. However, some smallpipes have a slight taper, which is sometimes inverted but for the acoustics, it is acting as though it is parallel. This doesn’t make all parallel bore pipes smallpipes as shown by the Grosser Bock its central European descendants. This leaves size as a critical feature as the conically bored Lowland and Border, Reel pipes, etc are not smallpipes.

The next question is does it have to have a specific reed type? I would say no, both double and single reed pipes would be classed as the same family with a common ancestor. We have lots of images, as well as artefacts from as far back as the Bronze age, including the double reeded Greek Aulos as well as the single reeded Egyptian double pipe.

This now leaves us with two branches of smallpipes; a single reeded family including Säckpipa, Boha, moldanky/Praetorius Dudey and the double reeded types which include the Musette de cour, Northumbrian smallpipes, Scottish smallpipes and maybe the hummelchen. It is the double reeded family that we now call smallpipes in the UK, both mouth and bellows blown.

Thankfully, we have an unbroken tradition of smallpipes in Northumbria and they became part of the of the folk revival in the 1960s and ‘70s. As well as an increase in awareness and playing of the pipes, there was also an upsurge in making and pipe-making classes started in Alnwick, with other classes following. In 1967, the publication of The Northumbrian Bagpipes by W A Cocks and J F Bryan, containing detailed engineering drawings of the instrument, allowed people with appropriate skills to be able to make pipes on their own without the guidance of a teacher. As the interest in amateur and professional making grew, so the network of communication and knowledge grew.

(example of a wide bore single reed bagpipe)

From the late 1960s, the folk revival in Scotland had also been gathering pace and, for the first time since their popularity declined in the 19th century, Scottish smallpipes began to make a comeback as they were featured in bands such as The Whistlebinkies and The Clutha. Being pioneers, they would use old instruments that they would get working as best they could. With this revived interest we see the formation of the Lowland and Border Pipers Society (LBPS) in the early 80’s.

(example of a wide bore single reed bagpipe)

The most significant factor in the development of the Scottish smallpipe revival, led by Colin Ross and other Northumbrian pipe makers, was the manufacture of instruments in keys that were suitable to be played with other instruments. In particular, those in the key of A (that is high A) became very popular with Highland pipers as the finger spacing was similar to that on the Great Highland Bagpipe. From this point, other high quality instruments became available, with Hamish Moore and Julian Goodacre among the early makers and developers. The Blowout would not be the same without the “D” Session with the majority of people playing Julian’s, Leicestershire smallpipe.

(example of a wide bore single reed bagpipe)

For someone wanting to start learning pipes, smallpipes are probably the easiest of routes into piping, mainly as the fingering is quite forgiving with less squeaks and squawks than you would get with a conical bored chanter as in Border pipes - as long as you learn to blow steadily. With instruments commonly available in the keys of F, G, A, C and D, it is sometimes confusing for someone who has very little or no musical experience to know what to order. The most important thing to consider is in what context you will be playing your pipes. For example, for someone in the Scottish Highlands, where the repertoire of folk instruments is heavily influenced by the GHB, then A mixolydian would be the most important key to consider. But if I were to turn up at the Blowout with just an A chanter, I would find very few people to play with as G and D are the most common keys.

Smallpipes generally play in one octave but the range can be extended with some sort of keyed system such as in the petit chalumeau on the musette de cour. A back thumb hole on the bottom hand is very common nowadays allowing the chanter to play the minor third. (c natural on an A chanter). There have also been developments in extending the range by utilising over blowing and also with arrival of the 3D printed Lindsay system chanters. Fingering systems can be varied, from the fully closed Northumbrian to half closed Scottish or French.

Wet or bellows? Bellows allows the use of a cane reed that is so finely shaved it would not last minutes with mouth blown pipes. Bellows pipes are also more stable whether you have cane or plastic reeds as you are only drawing in atmospheric moisture whereas with mouthblown, the reeds can get clogged up with constant moisture entering the bag. However, the main advantage of mouth blown pipes is the connection with the breath and the vibration of the instrument. I feel more at one with the whole process and it can feel quite meditative. Bellows are harder to master as breathing is natural as opposed to a mechanical process of pumping bellows.

Both the LBPS and Bagpipe Society have beginner/student sets of pipes available for hire, for those who would like to try without committing. I hope this is of some help to the intrepid beginner about to squeeze their first bag.

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

-

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

-

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

-

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!