The Bagpipe Society

The Sourdeline of Manfredo Settala, a Milanese inventor in 1640. Part 1

If there is one place I love above all in Italy, it is the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan. People come from around the world for the famous paintings of Leonardo, Caravaggio and Boticelli, but also for the strange and fascinating wonders gathered in this venerable house which was established by Cardinal Borromeo in 1611. Here there is a shrine enclosing a lock of blond hair from the beautiful Lucrezia Borgia as well as shells, beads and curious objects : this museum keeps the spirit of the «cabinets of curiosity» (or wunderkammer) of the Renaissance. I also like the Ambrosiana because it preserves some objects from the collection of Manfredo Settala, the awesome Milanese inventor who manufactured and perfected the sourdeline.

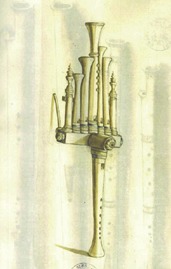

The sourdeline, sordellina in Italian, was a bellows blown bagpipe whose complexity was taken to the extreme by the canon Manfredo Settala of Milan, between 1630-1660.

I spent time in Italy last summer, trying to gather some evidence or concrete facts to establish the link between Zampogne and the «Grandes Cornemuses à Miroirs»1, the beautiful bagpipes that are the origin of the «chabrettes of Limousin». If the relationship between these two types of bagpipes is evident by the shape, sound, reeds and symbols, we still lack all the historical facts to complete the puzzle. And I still believe strongly that this connection lies somewhere between Milano, Padova, Ferrara, Mantova … and the Louvre, in Paris, together with a few scattered clues from the distant past.

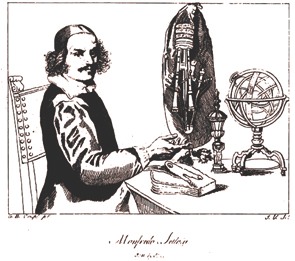

I was researching in a library of Ferrara, one of the most beautiful cities of North Italy, leafing through an art book about painting2 in Lombardy, when I discovered, amazed, the painting attributed to Carlo Francesco Nuvolone3 showing Manfredo Settala with his sourdeline. This was an original depiction of this exceptional instrument, known only by rare references and literary descriptions (fig. 2). Settala and his bagpipe were only known by a rather poor quality, clumsy engraving, which had been over-reproduced, contained in the Courtault Institute of Art in London4 (fig.3).

Manfredo Settala (1600-1680)

Manfredo Settala was an amazing man, an adventurer, scholar and a gentleman, an intrepid traveller in his youth, a collector and inventor, an artist and musician, who founded a remarkable museum in Milan. He was the son of a renowned scientist, Ludovico Settala (1552-1633), an author of books about medical sciences as well as a philosopher5 who was called ʺthe Aesculapius of his time."

After inheriting his father’s library, Manfredo accumulated strange objects, paintings by great masters, and surprising naturalia and exotica. His collection of paintings was exceptional and included some 85 works including some by Raphael, Tintoretto and Leonardo da Vinci. More than just a creative collector of «Wunderkammer», Settala was also a skilled craftsman, and had great expertise as a wood and ivory turner. He invented flutes with several pipes (and some ocarina made from a lobster claw), and he perfected the most complex bagpipe of his time, the sordellina (or «sourdeline» in French).

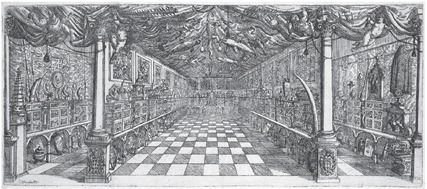

He installed his gallery (Fig. 4) in a new palace in Via Pantano in Milan, where he exhibited both his treasures and items he had made. He received there the most famous inventors of his time, such as Athanasius Kircher, who was also a philosopher and a musical instrument collector6. The museum of Via Pantano aroused great admiration among his fellow citizens, and two scholars drafted a comprehensive catalog of this « Galeria». Paolo Maria Terzago prepared the first version in Latin, printed in 1664, while Pietro Francesco Scarabelli gave an Italian translation in 1666.7

The young years of Manfredo

We know about the picaresque youth of Settala through the writings of Filipo Picinelli, a seventeenth-century author who wrote portraits of illustrious men of Milan.8 Settala had been a traveller in his younger years : at the age of fifteen he visited the Palazzo Ducale, in Mantova, where he discovered “the rarest wondersʺ9, the collection of fishes and exotic birds, fabulous minerals, exceptional paintings of Raphael, Tintoretto and Rubens collected by the Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga and his wife Eleonora de’ Medici. In Pisa that he became acquainted with mathematics, legal sciences and art of wood-turning, prompting admiration and the benevolent protection of the Duke of Mantova and his wife.

The young Manfredo wanted to follow in the footsteps of Ulysses and travel in the Mediterranean. A few months before this Odyssey (1622-1628) began, the first portait of Manfredo was10 painted by Daniele Crespi11(1597-1630), it still hangs in the Ambrosiana in Milan (fig. 5).

Settala wanted to discover the highlights of the Mediterranean. His travels take him to Sicily, the Levant, Cyprus and Gaza as well as “Nogroponte” (the Greek island of Evia) and Kandia (Peloponnese) where he “passed through the greatest dangers” including an attack of “Barbarians” and the Turkish fleet. He stays for two months in Constantinople, “observing the mosques, markets, and other more worthy curiosities”. Finally, with stops in Livorno, he returned to Milan.

The second life of Settala, the collector, the dilettante craftsman and scholar, begins on his return in 1628. Having attracted the attention of Cardinal Federico Borromeo (founder of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana of Milan) due to his knowledge of mathematics and history as well as his craft skills, he was appointed «Canon of the basilica San Nazaro» in 1630, situated at a few steps from the family home. Attached to the Accademia in Florence, he was received among the nobility of London, where he attended “the princes and high line characters.” He travelled extensively through Italy including many trips to Rome and Venice as well as becoming very skilled «He does what he wants with his hands. He became the Archimedes of our century, both in cutting subtle things, in the manufacture of flat mirrors, concave incendiary mirrors of enormous size, and musical instruments of all wonderful shapes12».

A “Book of Secrets” (Libro di Secreti)

«Our Manfredo, with many languages, is awaiting the translation and printing of his trips to Loiré (in France), to England, and many others. He is ready to print ‘A Book of Secrets’, filled with mysteries and curiosities13 ».

This book has been preserved. Composed originally of seven parts, three parts of the Codice Settala are in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, and two of the others are in the Biblioteca Estense of Modena.14 The two missing parts are lost for now. Each of these wonderful «books of secrets» consists of a collection of coloured drawings made from his museum (fig.6), some with a comment by Settala himself. Several of his instruments are depicted but the sordelline are missing (perhaps in the lost books).

How does a wealthy young man became a gentleman of fortune and then a man of the church, an inventor, a collector, an artist … here truly is a picaresque novel yet to be written.

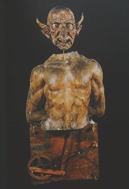

Some objects from Settala’s collection still survive in various museums including a mechanical devil, a spiky fish, a multiple flute and frightening shell masks as well as the armillary sphere depicted in his portrait.

The portrait of Settala by Nuvolone, and its three symbolic objects.

Settala is surounded by three objects that he had made: an ivory chalice, an armillary sphere, and the sordellina. Each of these objects has its own symbolical meaning.

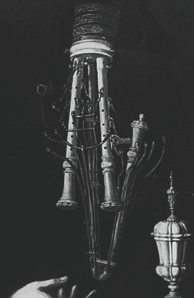

The sordellina remains a mythical bagpipe, mainly famous until now by the writings and drawings of Mersenne in his Harmonie Universelle (1636), and by two portraits of François Langlois, a famous virtuoso of this time. But here we can study a more accurate depiction in the portrait of Manfredo Settala by Nuvolone (fig. 2)15. None of the Milanese art historians had alerted musicolologists about this painting of Settala with his sordellina or realised it’s importance.

The Sordellina

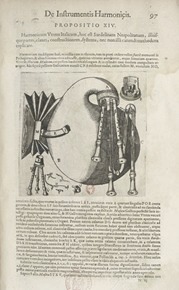

The Sordellina figures prominently in the centre of the painting, the pride of the inventor. If we observe carefully the drawing of sourdeline depicted twice by Mersenne16 (fig. 9) and compare it to the one by Nuvolone (fig. 10), it shows that these two instruments are almost identical, probably both made by the Canon of Milan.

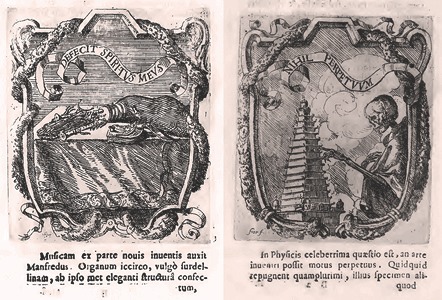

We know another representation of Settala’s sourdeline. It appears in his funeral tribute that was printed after his death, February 6, 1680. It is an engraving by Cesare Fiori (1636- 1702). The instrument, with its bellows placed on a table, is presented as an allegory of the breath of life. The epigram says : “Meus defecit Spiritus”, (My spirit fails) (fig. 11). Other allegories depicting objects invented by Settala are used in this booklet, as this perpetual movement (fig 12), also visible in the engraving of the Museum Septalanium, here accompanied by the epigram : “Nihil Perpetuum” (Nothing is eternal). (See next page.)

We can suggest an interpretation of the musical system of this sourdeline, through comparison of various sources, including Mersenne and Trichet, and also by the analysis put forward by Van der Meer17, Barry O’Neill18 and Frank P. Bär19. This will be the aim of my next article.

TO BE CONTINUED in the next ISSUE of «Chanter»…

Notes:

- Eric MONTBEL, Les Cornemuses à Miroirs du Limousin (XVIIe-XXe siècles). Essai d’anthropologie musicale historique. Dvd inclus. Chemins de la Mémoire - Ethnomusicologie et Histoire, L’Harmattan, Paris, 2013.

- AlessandroMORANDOTTI(ed.),IlritrattoinLombardiadaMoroniaCeruti,Skira,Milano,2002,p.166,reprod. p. 25. I thank Alessandro Morandotti for allowing me to use that photography of the painting, that he got in 1960. 3 On the attribution of the painting to Nuvolone, Crespi or another painter, see: Eric MONTBEL, « Le portrait de Manfredo Settala par Carlo Francesco Nuvolone. Un hommage au collectionneur et facteur de la sordellina”, Musique-Images-Instruments, 15, 2015.

- I thank Alain Framboisier and Florence Gétreau, who found the origin of this engraving.

- Silvia ROTA GHIBAUDI, Ricerche su Ludovico Settala: Biografia, bibliografia, iconografia e documenti, Biblioteca bibliografica italica. vol.18, Sansoni, Florence, 1959.

- See Antonio AIMI, Vincenzo DE MICHELE, Alessandro MORANDOTTI, Museum Septalianum, una collezione scientifica nella Milano dei seicento, Florence, Milano, Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, 1984, p.29-30.

- Paolo Maria TERZAGO, Musaeum Septalianum, Manfredi Septalae… Industrioso labore constructum…, Derto- nae, typis Filiorum qd. Elisei Violae, 1664. BnF S. 5536 et J. 5333; Paolo Maria TERZAGO, Pietro F. SCARABELLI, Museo, ò Galeria adunata dal sapere, e dallo studio del Sig. Canonico Manfredo Settala nobile Milanese…, Tortona, per li figliuoli del E. Viola, 1666, 1677. BnF, S. 5338 et FB. 22136. On the collection of musical instruments and the catalogues printed by Terzago and Scarabelli, see Franck P.BäR, «Le Museo Settala à Milan au XVIIe siècle: une collection d’ins- truments de musique à l’esprit français», Musique-Images- Instruments, 2, 1996, p.58-87; id., «Museum oder Wunde- rkammer- Die Musikinstrumentensammlung Manfredo Set- talas im Mailand des 17. Jahrhunderts», Für Aug’ und Ohr. Musik Kunst- und Wunderkammern, Wilfried Seipel (ed.), Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien – Skira, 1999, p. 58-71.

- I translated the youth of Manfredo from D. Filipo PICI- NELLI, Ateneo de I Letterati Milanesi, 1670, p.406-408.

- D. F. PICI

- In the catalogue by P.M. TERZAGO et P.F SCARABELLI, Museo, ò Galeria, op.cit. p.236we can read : « 7. Ritratto del Sig. Manfredo, mano di Daniello Crespo».

- Daniele Crespi died from the pleague in 1630. His master and parent was Giovanni Battista Crespi Il Cerano (1573-1632).

- «Viaggiando ha scorso si puo dire tutta l’Italia, condotti cinque volte a Napoli, undici a Roma, dicisette a Venezia, tre nella Sicilia, due in Sardegna, e una volta a Capo Bonifacio, a veder la pesca de i coralli. Egli di sua mano opera cio vuole ; divenuta l’Archimede del nostro secolo cosi nel taglio delle cose sottili, come nella fabbrica di specchi piani, concavi, ustori, di canocchiali di smisurata grandezza, e di strumenti musicali d’ogni forte opera maraviglie.» D. F. Picinelli, Ateneo de I Letterati Milanesi, op.cit. p.407.

- «Il nostro Manfredi, come possessore di molte lingue, attende alla tradittione, e stampa di i viaggi del Loiré, di quello d’Inghilterra, ed altri. Havend’egli preparato per dar alle stampe “Un libro di Secreti” d’arcane curiosita ben copioso.» D. F. Picinelli, Ateneo de I Letterati Milanesi, op.cit. p.407.

- Codice Settala is under the references Z 387, Z 388 et Z 389 in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana of Milan. The two others books in the Biblioteca Estense of Modena, are under the references GAMMA.H.1.21 and GAMMA.H.1.22, and can be read on line: http://bibliotecaestense.beniculturali.it/info/img/mss-tn.html.

- This painting was published by Alessandro Morandotti for the first time in 1996, then in 1999 and 2002. It then appears in the 2003 monograph on the family Nuvolone by FM Ferro. According to him, the painting was sold at Christie’s in London May 25, 1960 under No. 107, and it is no longer located since. Alessandro Morandotti, «Note brevi per Cerano animalista, Vermiglio pittore di figura e Carlo Francesco Nuvolone autore di ritratti», in Mina Gregori, Il Seicento lombardo: giornata di studi, Torino, Artema Compagnia di belle arti, 1996, p. 68-69, fig. 107; Alessandro Morandotti, in Mina Gregori (éd.), Pittura a Milano dal Seicento al Neoclassicismo, Milano, Pizzi, 1999, p. 271; Francesco Frangi, «L’étà barocca: Milano, Cremona e Bergamo», in Francesco Frangi, Alessandro Morandotti (ed.), Il ritratto in Lombardia da Moroni a Ceruti, Skira, Milano, 2002, p.166, reprod. p. 25. F. M. Ferro, Nuvolone. Una famiglia di pittori nella Milano del’ 600, Soncino Editore, 2003, p.194.

- Marin MERSENNE, Harmonie universelle contenant la théorie et la pratique de la musique, Paris, 1636; reprint, fac-sim., avec introduction de François Lesure: Paris, éditions du CNRS, 1986. The «Sourdeline ou Musette d’Italie» is presented pp.293 and 294. The same study and drawing are in the latin versionby Marin MERSENNE, Harmonicorum libri instrumentorum IV, Paris, 1636, p.97-98. The text is quite diffrent, with less details, but the drawing is better.

- John Henry Van der Meer, « La Sordelina : organologia e tecnica esecutiva », Libro per scriver l’intavolatura per sonare sopra le sordelline de Giovanni Lorenzo Baldano (1576-1660) ; reprint, fac-sim. (manuscrit Savona, 1600) : Savona, Associazione Ligure per la Ricerca delle Fonti Musicali, 1995, p. 73-105.p. 92-93.

- Barry O’Neill, « The Sordellina, a possible origin of the Irish regulators », The Sean Reid Society Journal, vol. 2, Mars 2002, p. 1-20.

- Franck P.BäR, «Le Museo Settala à Milan au XVIIe siècle: une collection d’instruments de musique à l’esprit français», Musique-Images-Instruments, 2, 1996, p.58-87.

Eric MONTBEL

- Data Processing Notice (GDPR)

@BagpipeSociety on X (formally known as Twitter)

TheBagpipeSociety on Instagram

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

BagpipeSociety on Facebook

Something wrong or missing from this page? Let us know!